Victimhood and the allure of "power-under"

Understanding trauma, agency, and what it takes to heal

Alfred Adler famously described two fundamental human needs: to feel a sense of belonging, and to feel a sense of significance. While I write frequently in this newsletter about our universal need for belonging, I fear I’ve devoted insufficient attention to our need for significance… our need to experience power, agency, and a sense that we matter. In particular, I fear I’ve underestimated how widespread our experience of powerlessness is… and how the quest for power—or more accurately, the desperate desire to avoid the devastating feeling of powerlessness—is increasingly driving our politics.

In particular, I want to unpack the implications of Steven Wineman’s observation, which feels central to understanding and responding to this moment:

When internalized powerlessness is paired with objective dominance, it creates a lethal dynamic in which we unwittingly respond to our own victimization by oppressing others.

So today I want to talk about victimhood, trauma, and power.

TL;DR: The central feature of trauma is the subjective experience of powerlessness. I believe much of our current dysfunction (authoritarianism in dominant culture; othering and disposability in social justice culture) is motivated by a desperate effort to reclaim agency in the face of feeling powerless. Thus, our movements must focus on providing opportunities to access agency and the felt experience of power-with (not power-over or power-under) if we are to be effective in responding to the rise of authoritarianism.

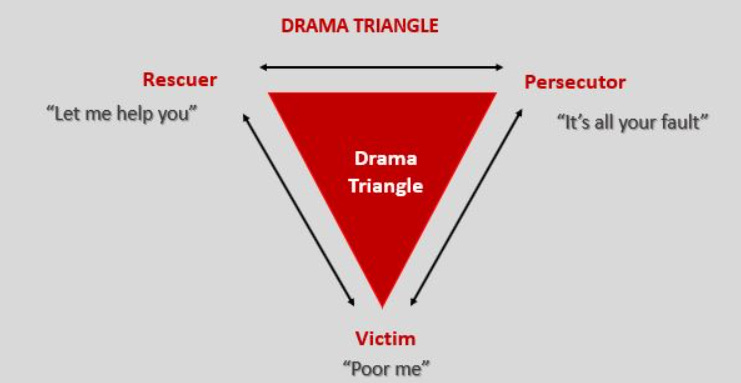

The Drama Triangle: a desperate bid for agency

I’ve been thinking about the concepts I’m trying to weave in this post for many years (see e.g. this post where I first tried to unpack what I called “victimhood and the paradox of power”). But the understanding that is crystallizing in me and that I’m trying to convey in today’s post is indebted to Steven Wineman’s brilliant self-published 2003 book Power-Under: Trauma and Social Change.

Here’s how I understand the logic flow (this is me talking, weaving/interpreting Wineman):

The defining experience of trauma is the feeling of powerlessness.

When confronted with experiences that trigger our past trauma, we often assume a role described in Stephen Karpman’s “Drama Triangle”: Persecutor (Perpetrator), Victim, or Rescuer. I think this provides a useful heuristic to engage the concepts I’m exploring today, and a more helpful frame for my purposes than the more common fight/flight/freeze/fawn responses often discussed in trauma literature.

In all cases the move is a desperate attempt to claim power in the face of a subjective feeling of powerlessness.

The Persecutor seeks to assert agency by stepping into power-over: you are making me do this.

The Victim asserts agency with a claim to power-under: I am being hurt and deserve attention and help; they blame the persecutor and try to recruit rescuers.

The Rescuer (that’s me!) asserts agency by being of service: we try to help the victim (doing for others what we wish they would do for us).

I think the Drama Triangle provides a useful prism through which to make sense of this current moment of rising authoritarianism: both its expression in dominant culture (visible in the rise of far-right nationalism that is increasingly fascistic in its expression) and its expression in social justice movement culture (via the phenomenon of “cancel culture”: what Kazu Haga et al call “a culture of disposability and othering”).

Victimhood from a place of domination: from victim to perpetrator (power-over)

It’s important to hold in mind that the central feature animating all of this is the subjective experience of powerlessness: this has powerful implications for the antidote (which MUST be about reclaiming agency and power in ways that do not perpetuate violence and domination).

This article by Lynne Forrest is my favorite deep dive into how the Drama Triangle operates, with a particular emphasis on understanding how the axis rotates around Victimhood. She explains why she thinks it is more accurate to call it the Victim Triangle:

No matter where we may start out on the triangle, victim is where we end up, therefore no matter what role we’re in on the triangle, we’re in victimhood.

She explains that most of us have a default “starting-gate” position on the triangle:

Our starting-gate position on the victim triangle is not only where we most often enter the triangle, it is also the role through which we actually define ourselves. It becomes a strong part of our identity.

Let’s start with those currently perpetrating domination and violence at a mass scale: this is Trump and Musk et al (as well as those authoritarians in power around the world: Putin, Orban, Erdogan, etc). They are Persecutors who experience themselves as Victims; it is no accident that Trump launched his 2016 campaign by declaring “I am a victim.” Trump’s claim to victimhood is core to his rise to power; an article in Politico called it “his one superpower.” Indeed, a recent research paper looked at his narrative strategy alongside that of Hungary’s Viktor Orban and coined the term “hijacked victimhood” as the central feature.

I think that’s giving Trump and Orban more credit than they deserve. While I agree that they have an intuitive sense that this “strategy” is effective, I don’t think it’s an act: Trump genuinely feels like he is the victim. It’s important to note here that the sense of victimhood can be real (they are actually victimized) or purely perceived: for Trump (and many Perpetrators) they are actually NOT the victims. But because they are so entrenched in the identity of victim, they are unable to conceive of themselves as perpetrators.

This is particularly dangerous: a sense of subjective victimhood when paired with objective power is the primary path to mass violence. They are unable to see or conceive of their own dominance. Wineman explains (explicitly reflecting on Israel/Palestine, writing way back in 2003):

The dominants lose sight of their objective power and experience the world as victims.

This entrenched self-understanding of victimhood helps explain Trump’s use of the phenomenon Jennifer Freyd coined as DARVO: a tactic (drawn from her research on intimate partner violence) of Deny, Attack, Reverse Victim-Offender. Trump, himself a serial perpetrator of sexual assault, is a master of this tactic. The accusation of perpetrator can’t penetrate his self-conception of victimhood… indeed it challenges that fragile narcissistic identity. Here’s Forrest:

[The Persecutor] overcomes feelings of helplessness and shame by over-powering others. Domination becomes their most prevalent style of interaction.

It’s worth going a level deeper to understand how this manifests and to understand the psychology of it. Wineman explains:

In order to acknowledge yourself as a dominant or an oppressor, you have to see yourself as an actor—as someone with the capacity to act upon others. If the essence of your experience is that you are acted upon in the world, it becomes difficult or impossible for you to conceive of yourself as having anything like this kind of capacity. If the essence of your psychological reality is that you are small and powerless, how could you possibly hold the power or the sense of agency to be able to dominate or harm anyone else?

This is what’s so hard to understand when we observe people with objective power (having access to and using “power-over” as domination): in the phenomenon I’m describing here, they are doing so from a self-conception of deep victimhood. Objectively they have power (which the rest of us can see clearly); subjectively they do not experience themselves as having power.

Victimhood from a place of subjugation (power-under)

Let’s shift focus now to the experience of those without objective power: people marginalized in our systems of oppression. I want to focus on how this dynamic plays out in social justice movement culture. There are two different dimensions I want to name here:

Victim to perpetrator: power-under. This is the same dynamic as above, but this time without access to objective dominance. In this case the victim is acutely aware that they don’t have access to dominant power (unlike in the first case, where the victim-turned-perpetrator is acting from lack of awareness of their objective power); however, precisely that understanding can mask their ability to recognize the power they do have, and/or their potential to cause impact/harm on others. Wineman explains:

Someone acting from an internal state of sheer powerlessness can have an enormously powerful impact on anyone in their path. This is the dynamic that I am calling power-under.

Victim: this is the role we imagine when we think of the term. Someone in need of help, lacking agency, feeling persecuted. In this role the victim does two things: blames the perpetrator, and tries to recruit rescuers. This points to the dual power in victimhood—particularly for a person with marginalized/oppressed identities. Blaming the perpetrator is a claim to innocence, appealing to a sense of righteousness. This in turn motivates the appeal to rescuers: as the righteous victim of injustice, compensation and repair is demanded. This is the appeal to being centered, to receiving care, to redressing wrongs. Particularly for those whom dominant culture relegates to the margins and deems outside of our ethic of collective care, this can feel like a powerful claim to inclusion and belonging.

However, even without going to perpetrator, remaining in Victim mode can also be a claim to power-under: wielding power from the subjugated position to insist on punishment for persecutors, on care from rescuers, etc. Danielle Carr explains the seductive logic here:

This wound provides our new identity, at once the thing that gives us the right to speak and the only thing we have left to say when we do… Our trauma is the guarantor of what we believe we are owed.

In social justice culture this shows up most commonly as someone with marginalized identities “cancelling” someone with more privileged identities (e.g. a woman of color accusing a White man of perpetrating harm, and insisting on punishment/exclusion from community). Because the objective power dynamics are so obvious (white man with dominant power = oppressor; woman of color marginalized from power = victim) it can cloud the actual dynamics at play… which may be much more complicated.

Again, it’s important to emphasize that all roles on the Triangle are matters of subjective experience: the victimization may be real or imagined (or a combination of both). Because it touches on our core traumas (triggering the feeling of powerlessness that pushes us into the Triangle in the first place) it can be very difficult to discern.

A word on rescuers…

This me 🙋♂️. Rescuers are core to making the Victim triangle operate… and many of us are drawn to social justice work. Forrest explains our motivation:

Rescuing is an addiction that comes from an unconscious need to feel valued. There’s no better way to feel important than to be a savior!

The downside, of course… is that we need someone to save. Which means just as victims recruit us, so do we recruit victims. And in order to have a victim, we also need a perpetrator: someone we are saving the victim from. Our claim to power is a claim to being needed, and we too don the mantle of innocence: I am not a perpetrator! And also subtly elevate ourselves over the victim (unlike you, I’m doing something!) Unfortunately, this claim to power also breeds codependence. Forrest again:

We may notice that we feel better when we are fixing someone else – it gives us a false sense of being in control which feels temporarily empowering. We may fail to recognize that our increased sense of power is often at the expense of the other, leaving them feeling disempowered and “less than.”

Oh. That doesn’t sound great.

Gender, victimhood, and authoritarianism

Victimhood in our society is deeply gendered by patriarchy: women are often cast in the role of martyrs (victims), men as perpetrators/actors. Rescuing also tends to be coded feminine (though of course any gender can play any role, and all of us can rotate through each role).

Under rigid patriarchal definitions of masculinity, men have a uniquely difficult time identifying as victims. To be a victim is to be without power; to be without power is fundamentally un-manly. According to patriarchal masculinity, victimhood is shameful. And yet men (like all people living inside systems of oppression) are victimized. So we’re stuck: it’s the paradox of feeling like a victim without being able to say “I’m a victim”… because our claim to identity and honor is defined in opposition to victimhood.

If the choice is victim or perpetrator, masculinity requires that men choose perpetrator. Many turn instead to rescuer… but doing so from a power-over position requires mental gymnastics. It requires women to accept the role of victim (which explains much of the anger directed at women who dare to assume agency and power), and it requires naming those in subjugated roles as the “true oppressors” (I believe this dynamic explains much of the backlash/hostility directed at trans people). In an article exploring the question “Why are White Men Stockpiling Guns?” Jeremy Adam Smith concludes:

Stockpiling guns seems to be a symptom of a much deeper crisis in meaning and purpose in their lives. Taken together, these studies describe a population that is struggling to find a new story—one in which they are once again the heroes.

Shame—and the desire to avoid it—thus becomes a driving force of authoritarian politics. Arlie Hochschild’s new book explains how Trump masterfully plays on shame and an unacknowledged sense of victimhood (manifest as resentment) to give his supporters a sense of pride and agency. She profiles one working-class white man in rural Kentucky who mused aloud:

If it’s such a privilege to be born a white male, what could explain me except my own personal failure?

Trump offers an answer in four steps, converting shame into blame... and pride.

Reframing loss (impersonal, systemic) as theft (someone did this to you)

Identifying the “threat” as an alliance between powerful elites benefiting subjugated “others” (both of whom are unjustly positioned above Trump’s audience)

Trump presents himself as the answer, punching back (imagining himself as victim) against elites, and returning what was “stolen” (by subjugated “others”: immigrants, people of color purportedly benefiting from DEI programs, etc.)

This allows people who are struggling (and men in particular) to adopt the banner of righteous victimhood: they see Trump as their chosen rescuer, and therefore must see “others” (racialized, marginalized) as their persecutors. Their vote/support for him is thus an act of agency in restoring their rightful place (and allowing them to escape the feeling of victimhood and access a sense of heroism).

There’s lots more to say about how these complicated dynamics play out, and how gender operates inside of these movements that is beyond the scope of this piece. But I do want to add that women in authoritarian movements also step into gendered roles, seeking male “rescuers,” claiming the power-under of victimhood (and often playing Rescuer roles with respect to children, a phenomenon visible in the “save the children” movement inside QAnon).

Building movements that build agency

My point in writing this post is to call greater attention to this phenomenon: to better understand both the psyche of those perpetrating from a place of powerlessness, and those utilizing power-under in ways that inadvertently perpetuate domination and prop up false oppressor/oppressed binaries.

If we understand trauma and the subjective sense of powerlessness as primary drivers of authoritarianism (and the authoritarian streak within movements for social justice) then our movements MUST do three things:

Offer people opportunities to exercise agency and experience their own power.

Support people to build more resilient and complex identities that hold room for both their oppressed and oppressor parts.

Support people in trauma healing.

The good news: we’re making progress on number three (e.g. Staci Haines’ The Politics of Trauma and Prentis Hemphill’s What it Takes to Heal are two recent books about how to build our capacity for trauma healing in the context of social justice work).

The bad news: we have a long way to go on building agency, and on supporting people in cultivating more complex identities that reject the false binaries of our systems of oppression.

I think the sequencing flows this way (agency and complex identities before healing) in part because accessing power and agency IS a key piece that allows us to experience more of our own humanity and support our healing from trauma. I think it’s a three-step process:

First we have to understand how we have been victimized (Wineman conceives of victimhood as a necessary “transitional” identity: understanding how we have been harmed by systems is essential to the process of politicization that enables transformation). This is about centering ourselves and understanding how we have been harmed (e.g. many men still do not understand their own victimization inside of patriarchy, and as such cannot escape it).

Then we have to locate the cause of our suffering: the systems of oppression that keep us locked in the false binaries of oppressor/oppressed, and activating the shame that keeps us stuck in the Drama Triangle. We have to strenuously reject any efforts that seek to blame the “other” for our plight.

Then we have to find ways to experience our own agency and power as actors capable of changing these systems… by working together in solidarity.

The good news is, more people are recognizing and turning attention to these imperatives (indeed, just yesterday a new podcast episode from Starhawk hit my feed entitled “Trauma and Agency”… I love co-arising emergence).

From victimhood to empowerment: escaping the Drama Triangle

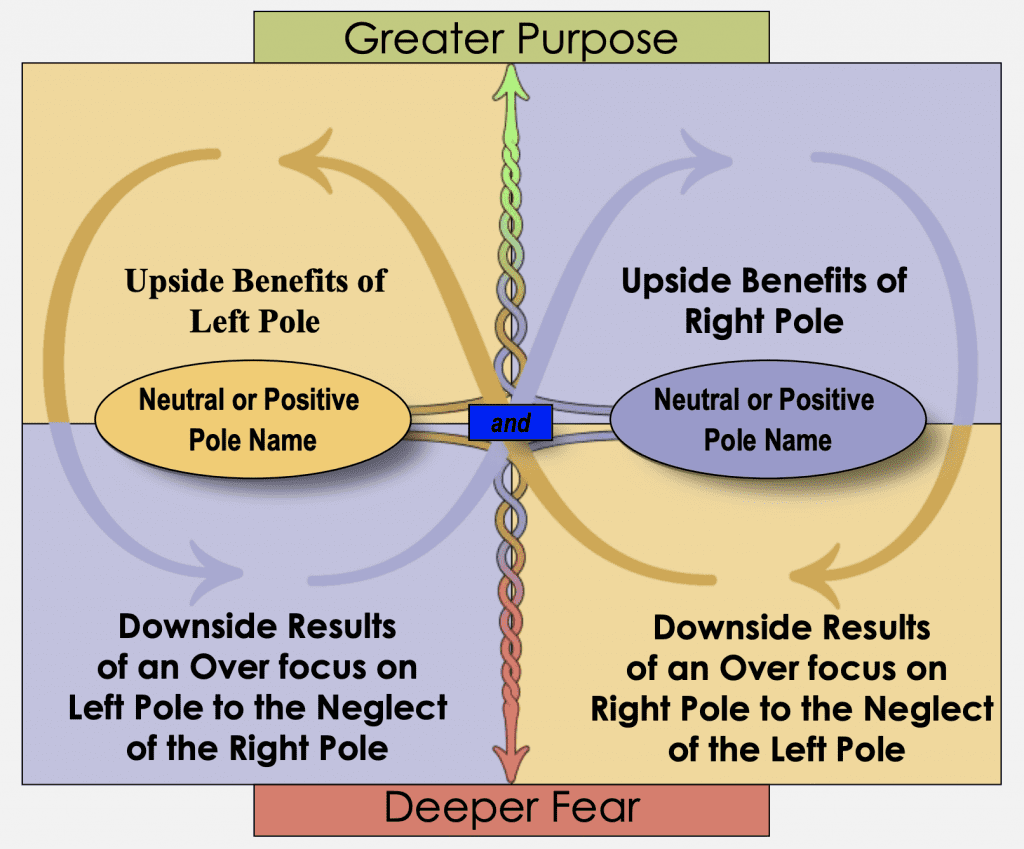

David Emerald proposed a framework he calls “the empowerment dynamic” for how to exit the Drama Triangle, with corresponding roles for each, as follows:

I think it’s a great framework and departure point (though I see the energy for action in the Drama Triangle coming from fear and shame rather than anxiety, and the energy for action in the Empowerment Dynamic coming from love and solidarity).

This is the individual/internal path to liberation: moving from victimhood to empowerment, claiming the agency and power that is denied us by systems of oppression. Wineman again:

One of the cornerstones of liberation is surely that people experience a sense of power and efficacy, and have the ability to control their own lives in a range of meaningful ways… Subjectively, liberation from oppression involves a straightforward progression from powerlessness to empowerment.

It is also the objective path to liberation (fractally: transforming ourselves to transform the world). As we decline to act from domination/power-over or victimhood/power-under and instead cultivate the capacity to act from agency/power-with… we are practicing liberation: what Bobbie Harro calls “the practice of love.” This is essential if we want to build more successful movements and broader coalitions. I think Wineman has it right:

What is probably most important is to develop programs and strategies for addressing the real powerlessness in people’s lives, and to do so in ways that don’t play to and manipulate power-under, but that… offer them ways to express rage and to gain a sense of power and safety that is not at the expense of Others.

This requires a deep commitment to the humanity of everyone: oppressors and oppressed alike. It requires acknowledging that all of us contain elements of both. Here’s Wineman, channeling collaborator Aurora Levins Morales:

We need to fully grasp the humanity of those who too easily become defined or treated as Other… If we agree to accept limits on who is included in humanity, then we will become more and more like those we Oppose.

We do this both as the only viable path to transformation for “them”… and as part of honoring our own humanity. As adrienne maree brown recently noted:

Part of our job is humanizing ourselves enough to see the humanity in everyone else.

I want to close it here, though there is so much more to say.

I want to write soon about Shadow integration: it feels core to so much of what this moment is inviting in us. I recently returned from a soul-confronting immersion with the Light Dark Institute looking at my own shadow, explored through the lens of kink and BDSM (profound technologies for shadow work, it turns out). And I spent two whole days interrogating my complex relationship to victimhood… so much more to say and to unpack in myself.

I’m curious how this lands, and how people see the implications for movement strategy. What should we be doing differently to respond to this authoritarian moment?