Today I want to write about liberation: what it takes to get free.

This post—like all my writing—is born out of my struggle to make sense of the world and to act within it. To find my people, to cultivate the skills necessary to move toward my vision. One of the biggest challenges I’ve confronted in this work is the ineffability of it: it’s incredibly difficult to put into words what I’m trying to do. And it’s really hard to practice—or build community around—something you can’t name.

I know I’m not alone. I have been fortunate to encounter many fellow travelers on this journey. And it has become clear to me over eight years of deep inquiry and practice that there is something definable we are doing; it does have core guiding principles; there are identifiable skills and practices that can support our efforts toward transformation. There are things NOT to do. And I know it would support me—and others like me—to try to name what those things are, to give us something to aspire to, and practice together. To refine, improve, and share. I think we can make it easier to build belonging.

So today I want to try to do three things: adopt a label that can help us orient ourselves; name the principles that guide our practice; and point to the skills needed to move toward our vision.

TL;DR: I think what unites those of us seeking to build belonging is a commitment to “liberatory practice.” This work follows five guiding principles:

Inner work is essential

Embodying the future we want

Transformation happens in relationship

Centering equity, attending to power

Centered accountability

And it’s not enough to have principles: we need partners with whom to collaborate. Creating these containers for transformation—communities of liberatory practice—is essential to navigating this moment.

The need for a name

One of my greatest sources of hope these days is the tremendous number of people really trying to transform. To be better humans. Perhaps the broadest heading here is captured in the idea of “doing the work.” This concept, popularized by Nicole LePera and others, speaks primarily to inner work, particularly healing from intergenerational cycles of trauma.

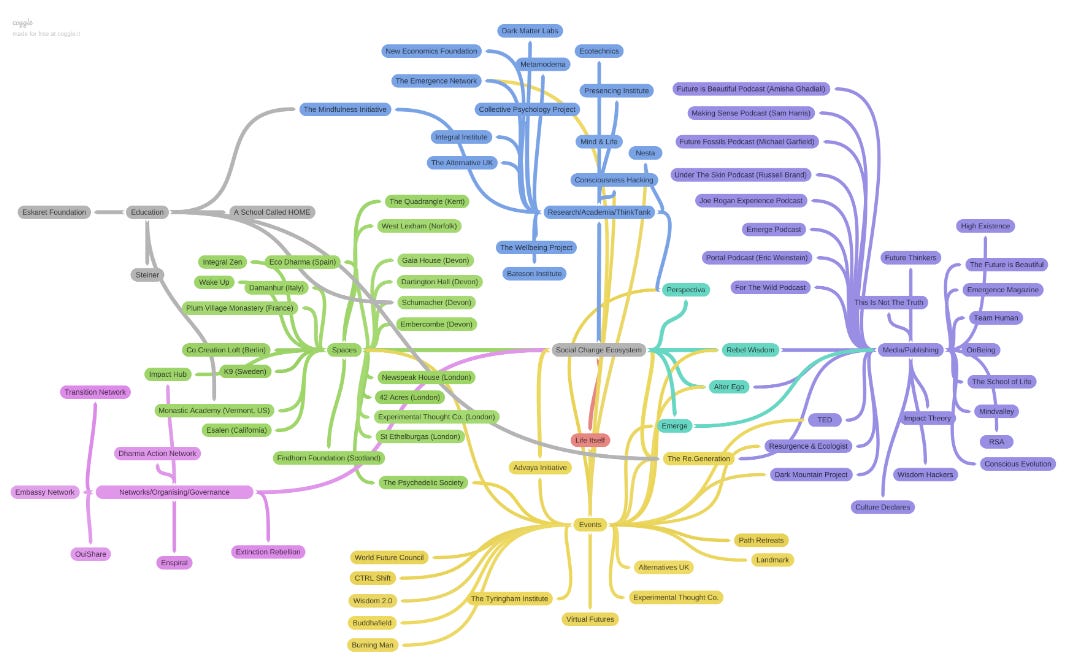

There is a companion field emerging primarily in organizational space, under the broad umbrella of “new ways of working.” This field—with terms like sociocracy, Holocracy, horizontal, teal, self-management—builds on the contributions of Frederic Laloux and others and has been popularized by podcasts and books like Brave New Work. Rufus Pollock led one of my favorite efforts to map/synthesize this emerging space with this ecosystem map of what he has called the “metamodern” movement:

In my view both of these emerging ecosystems are powerful and necessary contributions to transformation. And: there is a risk that “doing the work” in an inner context alone can become navel-gazing and spiritually bypassing. And “brave new work” that limits its inquiry to organizational structures and ways of working can risk downplaying or ignoring systems of oppression and how they shape our context. I find myself skeptical when the leaders and shapers of movements are primarily White. If a movement isn’t diverse, it tells me something is missing.

But there is a third and lesser-known field that I think has the potential to tie it all together: an emerging discourse, primarily led by women of color (and Black women in particular), trying to articulate a theory and practice of “liberatory leadership.” Liberatory leadership as I understand it seeks to provide an integrative framework that recognizes the fundamental interdependence of inner transformation, interpersonal transformation, and systems transformation.

So today I want to talk about what I’m seeing emerge under the auspices of “liberatory leadership” and how that framework can serve both to unite disparate efforts/fields toward transformation, and to invite more people to join us in “doing the work”: not only for ourselves or our organizations, but for the world as well.

Longing for liberation

I’ve been searching my entire life for ways of being and relating that feel in integrity with my commitment to building a world where everyone belongs. And for the last eight years in particular, I’ve devoted all of my professional energy to finding kindred spirits with whom to partner and build community: what I think of as “political home.” People who are committed to building a world where everyone belongs, who are committed to unlearning and deconditioning from our systems of supremacy, who want to collaborate across difference, to heal and grow together.

Unfortunately, here in the U.S. the large-scale political homes that do exist too often emerge in the context of electoral politics, where none of the labels speak to me. I don’t self-identify as liberal, and progressive doesn’t go far enough for me. Radical yes, but the term itself doesn’t tell you in which direction I’m radical, or what I mean by that. Abolitionist? Also yes, but that doesn’t really tell you what I’m for… and neither of those terms really capture the popular imagination. This absence of a name bothers me; labels matter! They help us find each other. As South African activist and elder Mamphela Ramphele notes:

Labels and language are always important. Who you say you are shapes who you are.

Of late I’ve found myself gravitating toward the language of liberation, following a long lineage of activists, practitioners, and theorists, nearly always people of color or those with marginalized identities. I like that it has in the title what I’m about (not only what I’m against). I like that the concept helps ground my vision of belonging in action. And I really resonated with Leticia Nieto’s recent offering connecting the two concepts:

This is what liberation is made of, a recognition that we belong.

In a political context, then, how about this: I am a liberationist: a person committed to building belonging.

Toward liberatory leadership (and practice!)

It was that yearning to find political home with kindred spirits that inspired the launch of Building Belonging, and my aspiration for it as a “community of liberatory practice.”

Liberation as a concept and practice enjoys a long lineage tracing back to abolition movements, where a tradition of Black liberation runs powerfully across time and place (in South Africa, e.g.) It also includes the 20th century liberation theology movement in Central America, and was popularized in popular education through the work of Paolo Freire. And of course it has provided a rallying cry for diverse movements: both to throw off the yoke of colonization, and for women’s liberation, queer liberation, etc. My own understanding and commitments take inspiration from the work of bell hooks, who may have coined the concept of “liberatory practice” in her classic essay “theory as liberatory practice.”

“Liberatory leadership” as a concept owes its emergence in recent years to the field-building efforts of a group of primarily Black women trailblazers: a co-arising emergence of people longing for different ways of leading and working, and asking similar questions. I want to name some of those who I find myself learning from (and sometimes with!) so that others can reach their own conclusions. I have found myself inspired and provoked by:

Trish Tchume is in many ways the initiator of contemporary field-building efforts around “liberatory leadership.” She played a key role in co-convening the collaborative Liberatory Leadership Partnership that to-date is the most comprehensive effort I’m aware of to define the term and consolidate the field.

Leadership Learning Community (and Ericka Stallings in particular, in partnership with Trish), curated and hosted a series on Liberatory Leadership back in 2021, and they have consistently been attracting and distilling some of the best work I’ve encountered trying to make sense of “liberatory leadership.” They also convened last year a “Liberatory Networks Community of Practice” facilitated by the wonderful Alexis Goggans that I was fortunate to be part of.

Change Elemental, and in particular the work of Elissa Sloan Perry (featured in the webinar above), and her new curated offering around Prefiguring Futures.

Susan Misra, who in addition to her long-time role with Change Elemental continues to steward liberatory work wearing her new hat at Aurora Commons (she was also part of the liberatory networks community of practice mentioned above). With Change and in partnership with Trish and others, she helped launch an inquiry into the qualities of liberatory networks.

Cyndi Suarez, in her personal capacity and in her recent past role as president of Nonprofit Quarterly, where she helped chronicle and weave many of the practices and practitioners helping shape this field, in addition to her foundational contributions distinguishing supremacist and liberatory forms and uses of power.

Mia Birdsong, in particular in her recent capacity curating Next River and their gorgeous offering of Freedom’s Revival.

Miki Kashtan, and her diligent work and deep practice stewarding the Nonviolent Global Liberation Community. This long essay is a great example of the depth and conviction that drive her work.

It’s not an accident that most of this work is led by women of color: under our systems of oppression, they are acutely aware of the work liberation requires. We (those of us with privileged identities) often have a harder time recognizing that we too are trapped, that we too need to get free. Yet this is the work liberation requires. I love the invitation attributed to Aboriginal activist Lilla Watson:

If you have come to help me, you are wasting your time. If you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.

“The privileged act of naming”

There’s a fine balance in trying to nurture emergence. Disruption and chaos is necessary to break with the old order: to rush to structure and new norms too quickly is to interrupt the necessary transition, and can risk preempting what has yet to emerge. Wait too long and chaos can wreak havoc, preventing us from seeing the emerging “islands of coherence” and completing the transition.

I’m a pattern seeker: I have a natural tendency to see threads and themes amid complexity. This to me is the role of theory at its best: an effort to distill principles derived from practice… so that others can engage, reflect, refine, and build. Like bell hooks, I reject the false binary between wisdom arising from lived experience and wisdom distilled from careful observation and deep thought. Both are essential, and in relationship with each other. To me the goal is always intentional praxis (and that elusive word I long for, which combines not only theory and practice but also vision/radical imagination).

As Brooke Richie-Babbage noted: frameworks are a crucial vehicle for spreading ideas, to encourage uptake. They are critical tools for transformation. We can’t afford to start from scratch; we must honor the wisdom of what has come before (without being limited by it!) It is my sense that we now have enough emerging clarity and consensus among practitioners of liberation to try to name and intentionally disseminate some core principles.

I also want to be careful—the limitations of the written word!—to convey my intent. I am not seeking to claim ownership over an emerging discourse, or to claim credit for ideas that are being explored in real time by a diverse collective. Nor am I asserting that my conclusions are the right ones: I offer this sensemaking as an invitation to collaboration and co-creation. This is the fraught work of what hooks calls “the privileged act of naming.” As always, the success of good theory is its applicability in practice: do you feel seen? Does this help you be more effective in your work? Does this resonate? Does it move us closer to transformation… and liberation?

I’m sensitive to the fact that I am trying to make sense of a body of work that is primarily led by people who don’t share my identities… and Black women in particular. Indeed, part of what I’m trying to respond to is a sense that this work is the exclusive province of certain identities: I don’t think that’s right. I see liberatory leadership as something all of us can—and I would argue, should!—aspire to.

That work will necessarily be different inside of the diverse bodies we inhabit: Black women will be subjected to very different pressures, expectations, and judgments than I might face in a similar role. The work we have to do to get free, therefore, will look both similar (we are all trying to enact the same universal principles) and different (my job might be to take up less space and project more humility: people with marginalized identities may need to take up more space and project more confidence). Having embodied examples that we all can aspire to is essential.

What do we mean by liberatory practice?

Part of what gives me confidence that the field is ready to take shape is the remarkable degree of consensus emerging across diverse practitioners in diverse contexts. Indeed, it was my study and experience synthesizing the field and stepping into practice inside Building Belonging that led to our core principles (now co-shaped and deepened in collaboration with a new core team), which reflect and engage with much of what I am discussing here.

I see broad agreement on a set of principles:

Inner work is essential… and inextricably connected to the work we’re trying to create in the world. We are interdependent: my liberation, your liberation, and global liberation are all connected. In Building Belonging we call this concept “I, We, World.” It’s about bringing our full selves… and co-creating the conditions for everyone else to show up fully and authentically. As Warren Nilsson and Tana Paddock wrote in their study of social change organizations:

The social realities that they seek to change are not purely external. They are in the room. (Emphasis in original)

Embodying the future we want. There are a couple components here that are essential: we must have a liberatory vision for the world we want to create… AND we must practice living that way right now in the present (echoes of John Lewis’ vision of beloved community). Cultivating and accessing these visions requires accessing multiple ways of knowing: “embodiment” here speaking to integrating head, heart, body, and spirit.

Transformation happens in relationship. This is connected to the points above: the goal is a world that reflects our inherent belonging, in interdependent right relationship to each other and all beings. This process requires spaciousness and commitment: the idea of “going slow to go fast.” It is both the goal AND the mechanism of transformation. As Peter Block reminds us:

The hardest thing for people to understand is that the relationship is the delivery system of anything you try to accomplish. (Emphasis in original)

Centering equity, attending to power. This is what Change Elemental calls “deep equity”: naming and navigating power dynamics, and working constantly to redistribute power with a reparative lens. Both to heal past/present harms and to support everyone in accessing their “power within.” This is also where I see the structural work of what many of us call “liberatory governance.”

Centered accountability. We are going to make mistakes and cause harm: it’s inevitable. Nearly all of us are colonized peoples living inside supremacist systems. Centered accountability is about committing to repairing ruptures when they inevitably occur, to acting in integrity with our values and supporting others in doing the same. We need each other to heal and transform. As bell hooks wrote in All About Love:

Rarely, if ever are any of us healed in isolation. Healing is an act of communion.

For a more poetic framing, the Liberatory Leadership Partnership offers a fuller definition here touching on many of these themes.

Fumbling toward liberation

I chose this title in homage to Mariame Kaba and Shira Hassan’s brilliant contribution to transformative justice Fumbling Towards Repair. I like the idea both of capturing what we do know (lessons learned) and gesturing toward places where we are still stretching and experimenting.

There’s one such edge I would add to the emerging field of liberatory leadership/practice that feels really important: liberatory work must include an aspiration and practice of working across as much difference as the container can hold. Race, gender, class, nationality, ability, etc. Much of the work thus far that has emerged has focused on distilling lessons from the practice and wisdom of women of color leaders (and Black women in particular). That’s essential; we have so much to learn by centering the experience of those most marginalized by our systems of oppression, whose voices and insights dominant culture has intentionally excluded.

It’s incredibly important to create liberatory space for marginalized people to breathe free from the weight of having to navigate whiteness (and male bodies). I’m glad that early efforts have sought to distill lessons free from those ubiquitous pressures. And: we can’t stop there. To be in liberatory practice across race and gender adds another level of difficulty, and exposes new work for all of us to do.

This is an edge to liberatory practice that we rarely touch: committing to deep collaboration and shared power across our foundational fault lines, with race and gender in particular. Nearly all of the experiments I’ve chronicled thus far have been intentionally curated containers featuring primarily or exclusively BIPOC people, and often primarily or exclusively BIPOC women. Again, I want to be clear that this is a both/and: we have so much to learn from those configurations, AND creating and experimenting inside multiracial liberatory space—specifically to include White people—is also essential.

This was always a founding objective for Building Belonging: to create intentionally curated multiracial, multigender, multinational space for us to grapple, to fumble toward liberation… together. I learn a lot from people who move through the world in different bodies and identities than me; I learn even more collaborating and working WITH people who are different from me. It invites me into deeper reflection about my own assumptions and biases and conditioning: a level of practice I can make the mistake of skipping in interactions with people who share common identities.

This remains one of my own toughest growth edges: aspiring to centered accountability in ruptures across lines of difference without falling into the familiar traps of under- or over-accountability… and inviting my collaborators to do the same. I’ve noticed how challenging it is for people with marginalized identities—even those committed to liberatory practice—to step into centered accountability with White men in particular, given the deep histories of trauma linking our identities with the systems we are trying to escape.

Putting principles into practice

One of my favorite things about Building Belonging is the opportunity to learn from/with people who are deeply rooted in practice, and experts in teaching concrete skills. In this context I’m really excited about the work my teammate Leonie Smith has been leading through her Care & Repair series (co-sponsored with her Vancouver-based Necessary Trouble Collective), and the collaboration she is working on with Kazu Haga around what they are calling Movements of Belonging. This is about putting principles into practice: it’s not enough to know what to do… we need to know (and practice!) how to do it. As Ericka Stallings notes,

This lack of knowledge about how to operationalize liberatory values exists because we’ve never actually experienced it, so we are almost imagining it into being.

This is the good news: thanks to the work of people like Trish and those profiled above, we are finally in a place where we can practice with greater intentionality and clarity. Thanks to the work of people like Leonie and Kazu, we can build the skills and capacities we need to practice liberation… to build belonging.

And more people are documenting their work and disseminating practices we can experiment with; I love for example this gorgeous collaboration curated by Trish and others called Calling In & Up: A Leadership Pedagogy for Women of Color Organizers (I find the lessons relevant for anyone aspiring to liberatory practice).

I want to close with a lovely quote from this essay by liberatory practitioners Ingrid Benedict, Weyam Ghadbian and Jovida Ross:

To build the world we want takes practice. Our everyday actions shape and grow culture, which ultimately shapes systems. By allowing ourselves to imagine what we really want, creating structures that serve that vision, and doing our best to repair the harm we inevitably cause along the way—we grapple, feel, stumble, fall, and get up and try again, transitioning our world into the one we want.

And of course: we need partners with whom to practice. Relationships strong enough to withstand the inevitable stresses and ruptures that come with trying to practice liberation inside supremacist systems. This remains a long-term aspiration I hold for Building Belonging: to help create larger scale political homes for the many people ready to engage in liberatory practice.

Tomorrow I undergo my second serious surgery in 12 months… this time for a combined ACL/meniscus tear sustained playing competitive Ultimate frisbee. Sigh. I haven’t been as diligent as I would like with my writing of late, and trying to listen to my muse while balancing other life responsibilities. This post has been percolating for awhile; I’m curious how it lands, any adjustments you would make to the principles, and in particular who else you see engaging in or creating containers for liberatory practice.

What an amazing post! Introduced me to a bunch of names of people whose work I wish I had time follow every thread of. I love the idea of identifying as a "liberationist" - it's what I'm FOR. Thanks again for your distillation, Brian. Much appreciated.

Brian, I very much appreciate your dedication to liberating ourselves, liberating our world, and doing it within the container of relationships. As a queer woman, I’ve learned that liberation begins with freeing myself from my own biases and clearing my windshield so I can better see where others are positioned. Thank you again for documenting this important work.