This is the second post in a 3-part series exploring the titular question: why does patriarchy persist? A reminder of the rough structure:

What is patriarchy, and why is it important that we understand it? (read here)

How are we socialized into it, and how does it hurt us?

How can we dismantle it (and replace it with something more conducive to human thriving)? (read here)

Today I’m tackling the second question: how does patriarchy harm us? Here’s what it boils down to (TL;DR):

Patriarchy forces the separation of human qualities into the artificial categories of “masculine” and “feminine”; equates masculine with male and feminine with female; and then elevates the male/masculine over the female/feminine.

Patriarchy forces men to deny their need and capacity for relationships and connection, and forces women to deny their need and capacity for a strong sense of self and autonomy.

Then patriarchy shames each of us for desiring what we cannot have, and punishes us for trying to get it.

There’s a lot here, and the layers are deeeeeeep. Let’s get to it, and unpack each of these points in turn.

I. Patriarchy forces the separation of human qualities into the artificial categories of “masculine” and “feminine”, equates masculine with male and feminine with female, and then elevates male/masculine over female/feminine.

One of the things I really struggled with as I got into the literature on patriarchy was trying to tease out the differences between biological sex characteristics, gender identity, gender expression, and sexuality. I won’t get into all that here, but it belatedly occurred to me that one of the reasons it’s so difficult and confusing is because we tend to equate/conflate male (sex, and gender) with masculine, and female with feminine.

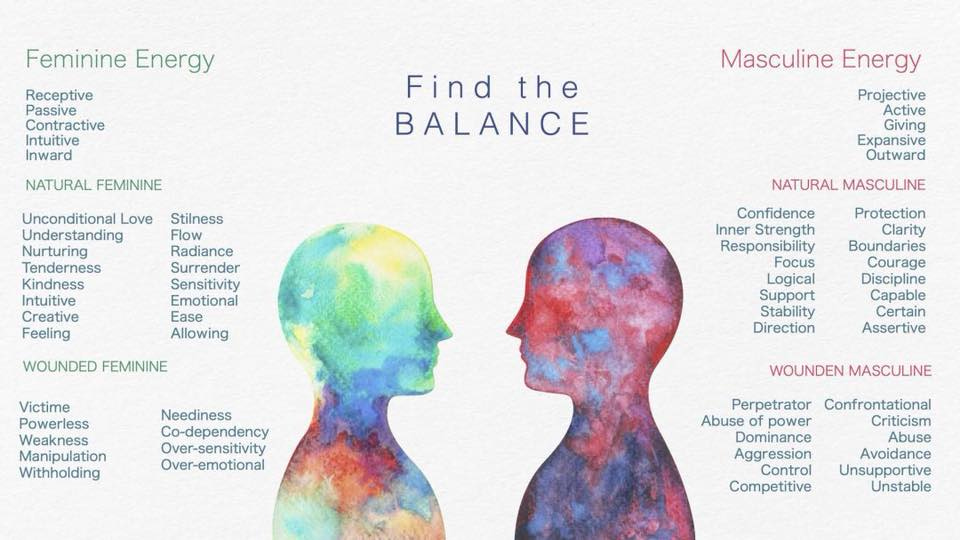

But of course every human has both attributes that society has deemed “masculine” and attributes that society has deemed “feminine”: they are parts of a broader human whole. This graphic (shoutout Miguel Dean) does a really nice job of making the point.

As Indian yogi Sadhguru reminds us:

A complete human being is in equilibrium between the masculine and the feminine.

The artificial split between masculine and feminine (distinct from the biological difference between male and female) is what Diane Musho Hamilton has called “the most fundamental duality.” As Donna Pendergast and Sue L.T. McGregor note: “A distinguishing feature of patriarchy is that it creates dualisms about every aspect of the world.”

Nonbinary artist and activist Alok Menon puts it this way:

patriarchy is the institutionalization and policing of the gender binary. patriarchy is the very creation of this thing called "male" and this thing called "female" which must always exist as mutual exclusive and oppositional states of being.

For the record: I am strongly against gendering human attributes (if we must categorize them, let’s call them “sun” and “moon”, or red and blue). I think it causes no end of harm. If we accept that full humanity requires both, any effort to associate one set of attributes with a particular sex seems to me counterproductive. Some people express more affinity for traditionally “masculine” attributes/traits, and some for more feminine. But it turns out that our propensity to express these attributes has little if anything to do with our biological sex, and almost everything to do with how we are socialized into our gender identities. Moreover, the science is increasingly clear that even our understanding of biological sex is woefully inadequate; we now know that there are a wide variety of other “sexes” (seriously, this article is mind-blowing).

I struggle with this all the time trying to raise our two daughters. Even in progressive Seattle, people can’t help but gender them and their activities: the tyranny of social expectation. I notice it in myself all the time, and in other parents at the playground. Almost without exception parents give boys more leeway to rough-house and climb, and girls are subtly and not-so-subtly reminded to "be careful” or “get down from there.” It was interrogating this phenomenon that prompted Lise Eliot to conclude that there is no real evidence of gender difference in babies. She argues persuasively that the appearance of gender differences in adults is the result of a self-fulfilling prophecy. The way we treat our children in turn creates the very gender differences we think we are responding to.

Sigh. I love this page from a book we’re using to teach responsible sex-ed to our four-year old:

Having first created the categories of masculine/feminine and then imposed them on men/women, patriarchy then completes the move: elevating men over women. It does this first by valuing supposedly “masculine” traits (power, strength, courage, assertiveness, independence, etc), and then — lo and behold — finding those traits “naturally” in men. So we end up in a society that systematically privileges masculine traits… and the men who supposedly embody them. And more: we systematically devalue and even disparage traits that we deem feminine (nurturance, interdependence). It’s a short path from devaluing the feminine to devaluing women. Terry Real, among my favorites in understanding men and masculinity, puts it this way:

The essential dynamic of patriarchy is that the masculine holds the feminine in contempt.

And of course, as we’ll discuss in the third point below, it’s even more complicated than that: men are punished for showing feminine qualities, and women are punished for daring to perform masculinity (not to mention anyone who attempts to defy the gender binary entirely). Enforcement mechanisms are swift and brutal.

II. Patriarchy forces men to deny their need and capacity for relationships and connection, and forces women to deny their need and capacity for a strong sense of self and autonomy.

It was this insight — the core thesis of Naomi Snider and Carol Gilligan’s mind-bending new book “Why Does Patriarchy Persist?” — that inspired me to write this series. I almost had to pull over the car when I first heard it articulated in a podcast interview: yes. This is exactly right, and deeply resonant with so many other themes that I’d struggled to integrate into any sort of coherence.

Maya Salam sums up their argument:

Patriarchy harms both men and women by forcing men to act like they don’t need relationships and women to act like they don’t need a sense of self.

The first part resonated directly with my lived experience: yes. I too have been taught not to “need” anyone, to be an island unto myself, to project invulnerability. Mark Greene has done great work chronicling what he and others have called “the man box”; I won’t belabor the point here. I highly recommend the documentary The Mask You Live In for an accessible and compelling portrait of how hard it is to navigate boyhood in America. (I often pair this with the outstanding Feminist on Cellblock Y to see the repercussions of this system in adulthood, as seen from inside a maximum security prison.)

Men have intimate and intuitive experience of the pain this causes, though we don’t often have the language or understanding to name it. This recent viral post named the problem in an interesting way: Men Have No Friends and Women Bear the Burden.

Obviously I have less direct personal experience with the prison patriarchy creates for women, but the point about denying oneself resonated deeply with so many of my interactions with women I love. Around the same time I found Gilligan/Snider I watched the Joy Luck Club for the first time, and this scene on how women perpetuate this particular insidious aspect of patriarchy across generations does such a beautiful job making the point.

Gilligan and Snider’s insight also reminded me of one of the most provocative assertions from Esther Perel’s work on intimate relationships and our sexual lives.

Love rests on two pillars: surrender and autonomy. Our need for togetherness exists alongside our need for separateness. One does not exist without the other.

There’s the paradox: we need to be separate (have a sense of self) and together (exist in relationship). Patriarchy conditions women to lose their sense of self, and men to lose their capacity for relationship... small wonder it’s so difficult to build a lasting relationship. Women struggle to express desire and experience authentic intimacy because it requires them to “own their wanting”… which is uniquely difficult to do in a patriarchal society that systematically devalues their desires (and themselves). Women are encouraged to subsume their desires into the whole (the family, their male partners, society). Men struggle to express love and experience authentic intimacy because we have been socially conditioned not to express our needs and emotions, or even to acknowledge that we have them. Terry Real again: “The essence of traditional masculinity is invulnerability… and disconnection.”

And of course this is brutal from the perspective of parenting. The absent/abusive father trope makes great sense in this light. But we often don’t fully appreciate the dangerous impacts on mothers who to this day do the brunt of the child-rearing. bell hooks describes the challenge facing even the most well-intentioned women in patriarchy: “Most females are encouraged to learn relational skills, yet damaged self-esteem may prevent us from applying those skills in a healthy manner.” (Mother wound, anyone?)

The implications here are profound. Men need to develop more relational capacity, AND encourage and support the women in their lives to cultivate a more autonomous sense of self. Women need to develop and protect a stronger sense of self, AND support the men in their lives to cultivate stronger interpersonal relationships. I will return to this in section three of this series (how we dismantle patriarchy), but the key takeaway is this: we ALL have work to do.

One more piece here. Arnina Kashtan (via her sister Miki) offers a really nice visualization of the raw deal each of us are given when born into patriarchy. It is this choice: freedom and autonomy (a sense of self) or connection and belonging (being in relationship).

Women are socially conditioned to give up their freedom in exchange for belonging; men sacrifice belonging for their independence (generalizing, of course). It’s a Sophie’s choice: what each of us deeply wants—and needs—is the integration of both. To bridge the false binary; Arnina calls this the star of life:

Yes please! In the final post I’ll discuss how we can live into that star.

III. Patriarchy shames each of us for desiring what we cannot have, and punishes us for trying to get it.

Patriarchy is enforced through violence. As Denise Comanne noted: “Domination is always accompanied by violence, which can be physical, moral, or in the realm of ideas.” For women — or anyone who deviates from rigid gender norms — this statement is obvious: anyone who has had to think twice about walking alone at night understands intuitively the omnipresent threat of male violence. Men too understand this: most male physical violence is both perpetuated by and targeted against men (a 2013 study found that men globally committed 95% of homicides, and were 79% of victims).

But I’m not only talking about violence out there in the world: it starts in our own homes, and in ourselves. bell hooks describes the process.

And of course, following Gilligan and Snider above, patriarchy demands that girls kill off part of themselves as well: their autonomous self.

In many cultures in the world today—including America—the dominant mode of parenting is through expressions of power, control, and coercion, often enforced through physical violence. It wasn’t until LAST YEAR (2018) that the American Academy of Pediatrics formally updated their guidance to recommend against spanking children; in many states corporal punishment is still permitted in schools. Kids learn quickly that it is okay to enforce rules and punish transgressions with violence: might makes right. These punishments affect boys and girls alike. Boys who are too feminine are quickly brought to heel; so too girls who are too masculine (note: this is changing, mercifully, in real time, and is one of the sources of optimism that the rotted edifice of patriarchy is finally crumbling).

But it isn’t only violence: it’s the threat of violence, and the use of shame. Michael Kaufman’s “The 7 Ps of Men’s Violence” is an outstanding read in its entirety; here’s a taste:

Men’s violence against women does not occur in isolation but is linked to men’s violence against other men and to the internalization of violence, that is, a man’s violence against himself.

This last point is worth sitting with for a moment. Increasingly, we rightly focus on the obvious damage of men’s violence against women. We occasionally acknowledge men’s violence against other men. But we rarely address men’s violence against themselves, and its relationship to these other more visible forms of violence. And I don’t mean just suicide (though that remains epidemic among men). Rather it’s about how male pain is transferred onto others.

A line attributed to prison abolitionist Mariame Kaba has stuck with me since I first encountered it: “No one enters into violence for the first time by committing it.” I remember finding this same sentiment in bell hooks, and it at once seemed so obvious and yet had never occurred to me. Challenging our popular conception of men as oppressors operating from a place of power, she says instead: “many victimize from the location of victimization."

This Key & Peele skit hits the perfect note — it’s actually too real to even be funny.

Men police gender conformity through violence; women police it through shaming.

Brené Brown, probably the foremost researcher of shame right now, explains that "messages of shame are organized around gender”, and offers this:

Men's shame is not primarily inflicted by other men. Instead, it is the women in their lives who tend to be repelled when men show the chinks in their armor.

Women often express violence less through physical force but through shaming, for that is the primary mechanism through which girls are punished and socialized for deviating from gender norms. Shame is thus both a form of violence itself and a cause of further violence. For men shame—and the desire to avoid it—is a primary driver of violence. As Jacques Verduin observed:

Anger is a second emotion. Fear, shame or sadness are underneath it. Violence is learned. No one is born armed and dangerous. We can unlearn it.

James Gilligan’s work on male violence remains seminal, particularly on the complex relationship between shame, guilt, and violence (this paper is an intense read).

Shame is an insidious force. As bell hooks notes (again! Really, just read everything she’s ever written and I think we’ll all be free):

Not only does patriarchy cause us harm, but it then shames us for wanting to repair the harm. It’s worth quoting Naomi Snider at length here, because this is a super subtle and absolutely devastating point:

The initiation into patriarchal manhood and womanhood subverts the ability to repair ruptures in relationship by enjoining a man to separate his mind from his emotions (and thus not to think about what he is feeling) and a woman to remain silent (and thus not to say what she knows). Thus, gender creates the ruptures that cannot be repaired. The masculine taboo on tenderness, like the feminine taboo on self-expression, opens the way to a range of relational violations and betrayals. At the same time, by shaming a boy’s expressions not only of hurt but also of care, by making it risky for a girl to say what she is actually thinking and feeling or to know what she does and doesn’t want, these gender codes subvert our ability to recognize and repair the ruptures in relationship, not only those we suffer but also those we inflict.

To make their point, they refer to this video on the “still-face experiment”, in which a mother and her infant initially interact happily, before the mom abruptly shifts to a deadpan expression. It’s a riveting—and difficult—watch, and under three minutes. Take a look (spoiler alert: they reconnect).

There’s a lot going on here, but basic points are:

We’re wired for connection

Disconnection is painful

We will resist disconnection and seek to reconnect

If repair isn’t possible, we despair, and move to detachment (sever connection)

As children socialized into patriarchy we go through these same phases (albeit perhaps not as viscerally). But the particular viciousness of patriarchy is it shames the move to repair. This is critical, because we can recover from harm… IF we reconcile and heal. If we can’t repair, only then do we despair and close down. This is the mechanism that enables patriarchy’s persistence in the face of all our resistance. Gilligan and Snider:

The persistence of patriarchy is contingent on the move from protest to despair and detachment.

I have absolutely felt this in my own life, where I’ll do something shitty and then find it super hard to just admit that fact. What’s so hard about owning up? It’s showing vulnerability, which is coded feminine, which I’ve been conditioned to know will be punished.

Nora Samaran’s new book, based on this outstanding viral essay, is the hands-down most sophisticated treatment I’ve seen on the gendered dynamics of shame and violence in the context of our upbringing. She brilliantly interweaves attachment theory to explain how patriarchy encourages us — in deeply gendered ways — to detach (makes sense: this is the science of “attachment” theory). The whole essay is incredible… I’ve read it several times, and each time I go back I get something new and deeper out of it. Here’s one piece that is really powerful:

If you have shamed something in yourself – like a normal need for intimacy – so early and so completely that you don’t even notice you are doing it, you will interpret that same need as shameful when you see it in others.

Here she’s talking about the typical man shaming a woman’s desire for closeness (the “needy” trope). But I think it’s equally powerful in same-sex scenarios where women shame other women for assertiveness and independence, or where men shame other men for seeking close relationships.

A final note before I close: I realize I haven’t talked much about other identities and their interplay with the dynamics of patriarchy : race, sexuality, ability, etc. So just to state what should be obvious: these all interact in important ways with everything I’m describing here. The pressures and stereotypes associated with Asian masculinity are very different from Black masculinity; black women and white women face very different social pressures and rewards; so too with gay and straight; cis- and trans;, etc. The point here is to describe the general dynamics, and hopefully the reader can recognize their particular in the universal.

Lastly: I know this series is long and dense, and that I’m not being very newsletter-friendly. I promise it won’t last forever; thanks to those of you who made it this far. If you did, I would love feedback. Almost there! Next up is the reason I’m spending all this time in the first place: how do we dismantle patriarchy, and what comes next?