I want to use this newsletter to explore the puzzling durability of a system that has now characterized human relations for 8,000-10,000 years. I want to complicate the obvious answer—that men benefit from this system and thus have no incentive to change the status quo.

There’s a lot here, so I’ve decided to break this into several posts. The flow will be roughly:

What is patriarchy, and why is it important that we understand it?

How are we socialized into it, and how does it hurt us? (part II available here)

How can we dismantle it (and replace it with something more conducive to human thriving)? (part III available here)

Today I’m tackling the first question: what is patriarchy? Here’s what it boils down to (TL;DR): Patriarchy lives within each of us. We made this system. We can unmake it.

I feel a need — as a cisgender heterosexual able-bodied white American man with class privilege — to justify why I’m writing this. But I also find myself resisting that urge.

The very fact that those identities coupled with a call to #SmashThePatriarchy seems counterintuitive is precisely the problem I am trying to address. The fact that in general (and I’m painting with a broad generalizing brush here) we express surprise that men might be interested in dismantling patriarchy speaks, in my mind, to our collective misunderstanding of what patriarchy is, how it operates, and how we might defeat it.

I remember my excitement—and subsequent disappointment— when I first encountered the Combahee River Collective Statement. The whole thing is absolutely brilliant: I found myself nodding along: yes, yes. Then I got to the penultimate line, seemingly appended as an afterthought, a quotation attributed to feminist scholar Robin Morgan:

I haven't the faintest notion what possible revolutionary role white heterosexual men could fulfill, since they are the very embodiment of reactionary-vested-interest-power.

And it struck me. In the nearly 50 years since Morgan wrote that (in 1970), the dominant discourse in feminism really hasn’t made much progress in answering that implicit question.

There are strands within the tremendous diversity of feminisms that challenge the dominant discourse and in my view offer a path forward. I am drawn to radical black feminist traditions, as embodied by bell hooks, e.g., and indigenous feminist traditions (as currently expressed by Kim Tallbear, Susan Deer Cloud, and Kimberly Dawn Robertson, e.g.) But though I identify with much of what is expressed by these women and others, it of course does not represent my experience as a white man in America.

So I want to offer in these posts two things: a synthesis of the best thinking I’ve encountered on a complex subject (often from queer women of color), as interpreted through the lens of someone who moves through the world holding the opposite identities.

Of course this is fraught, and super hard. My greatest weakness (well, one of the ones I’m aware of, anyway) is an over-reliance on my brain, on the illusory hope that I can somehow think my way out of patriarchy and other systems of oppression. But as adrienne maree brown so eloquently reminds us:

release any belief that your mind will liberate you from patriarchy. the change required now is not something you can learn or do with your mind alone. it is something you must practice with your body, emotions, soul. only consistent practice will rewire your mind and liberate your life.

Sigh. As I am humbly reminded every week in therapy… she’s right. You can’t learn how to throw a baseball by reading a book. Gotta get out there and toss it around a bit… and, inevitably, screw up. Then learn. Improve. And try again. With that context: let’s take up adrienne’s invitation to “work on excellence” together.

I understood—before I had words or concepts to express it—that American gender norms were oppressive. I learned by elementary school that it wasn’t okay for boys to cry or show weakness, or god forbid, to be feminine. And that much of this pressure—often enforced through violence or the threat of violence—came from other boys and men, including their own fathers. It’s no accident that in one of the iconic movies of my boyhood “Sandlot” (which came out when I was 11, just entering middle school) the most vicious insult is to accuse a boy of being like a girl.

But most of the discourse I encountered as I developed a political consciousness in adolescence and college spoke about the female experience of gender oppression. Which made great sense to me, but didn’t really speak to my experience. So it was a truly transformative experience when I first read bell hooks’ The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love, and she introduced me to the concept of patriarchy. The whole thing is a tour de force, but let’s start with this bold statement:

Patriarchy is the single most life-threatening social disease assaulting the male body and spirit in our nation.

I’ve spent several years now trying to sift through the layers behind this assertion, and the essential paradox it presents. The paradox is this: we know patriarchy hurts women. If we accept that patriarchy also hurts men… then how can we explain the persistence of a system that harms everyone?

That is the question I will explore over the next few posts. Today let’s start with the basics.

WHAT IS PATRIARCHY?

I. Patriarchy is invisible and all-encompassing.

We are all born into it and adopt its logic unconsciously: it is the water we swim in. As Charlotte Higgins notes:

Patriarchy’s particular power is its capacity to make itself as invisible as possible; it tries very hard not to draw attention to the means of its endurance.

Margaret Heffernan reminds us: “As long as it remains invisible, it is guaranteed to remain insoluble.”

So let’s try to make it visible: let’s talk definitions. What do we mean when we say “patriarchy”? There is no standard definition. The best I’ve been able to come up with is adapted from bell hooks, Gerda Lerner, Miki Kashtan, and John Bradshaw, in my view among the best thinkers on the subject. Three key features stand out to me.

Patriarchy is the institutionalized political-social system of male dominance.

Patriarchy is an ideology: it presents itself as natural and therefore immutable; a logical hierarchy of power and order.

Patriarchy has no gender: we are all complicit in upholding the system.

Let’s unpack each of these in turn.

1. Patriarchy is the institutionalized political-social system of male dominance.

There is a lot in this sentence, so let’s walk through the components.

Patriarchy is a system; it is not about individual behavior.

That system is institutionalized; it is represented in the very structures of society (this is the more common dictionary definition of patriarchy, which equates the system with men holding positions of power).

It is both political and social. We know we have never had a female president here in the United States: that’s institutionalized political patriarchy. But it also is in our social lives, starting with our households and family life; indeed, the two spheres (political life and social life) are inextricably connected.

Patriarchy is predicated on domination and control.

The first two points should be fairly straightforward, so I won’t spend much time there. The third point is more subtle and I will get into it in more depth in the next post (how are we socialized into patriarchy, and how does it harm us). But for now suffice to say that we cannot limit our understanding of patriarchy purely to politics or to formal institutions—it is much deeper and more insidious than that. The fourth point merits some elaboration here, because it provides some context for what follows.

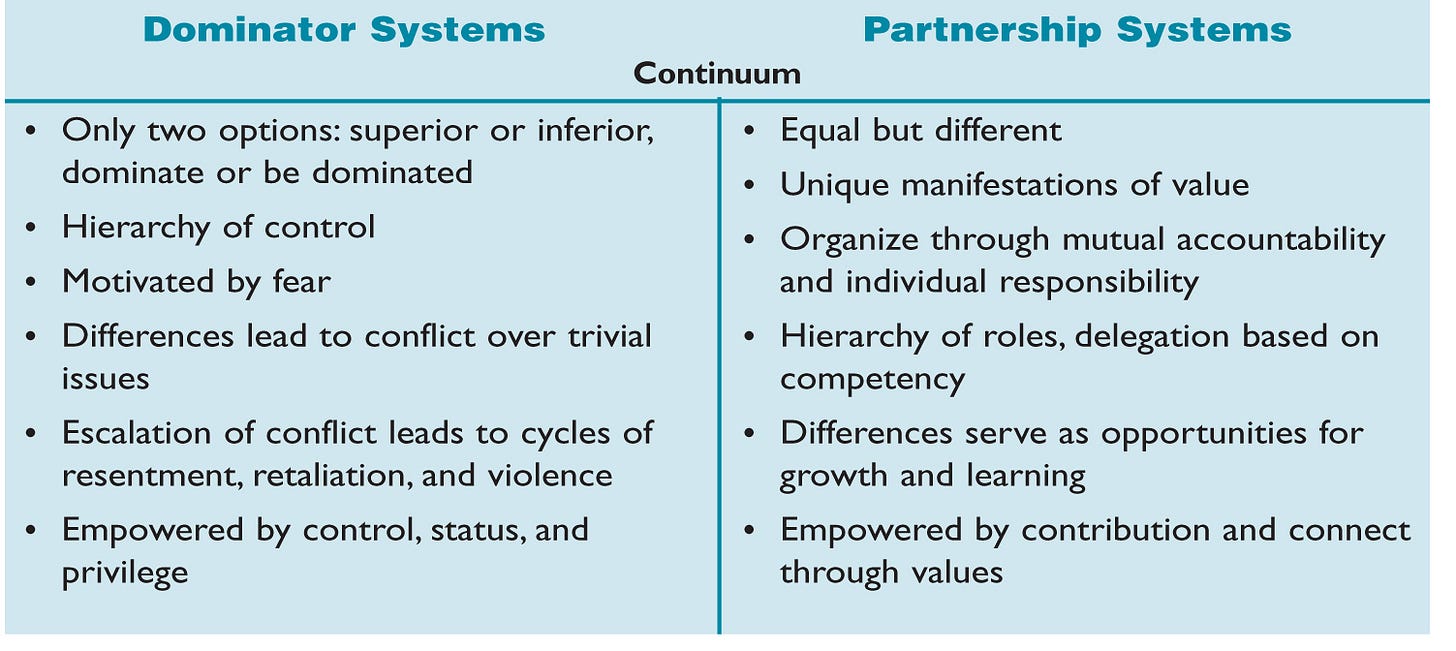

The core feature of patriarchy—and therefore of its various offspring—is domination. Of men over women, of masculine over feminine, of strong over weak. And because patriarchy depends on a rigid binary to enforce gender roles, it also privileges cisgender above trans, straight above gay, etc. Riane Eisler offers the best treatment of this subject in her writing on systems of domination; her groundbreaking The Chalice and the Blade speaks to the gendered origins of what she calls “dominator cultures.”

The connection between domination and control is straightforward; to dominate something is to control it. Most scholars and theorists trace its origin in the context of patriarchy to the need to control women’s reproduction (how else to confirm paternity?). This “need” emerged roughly concurrent to the emergence of global agricultural practice and the accumulation of assets (land) to pass on to heirs. This short blog provides an accessible summary of the theory; this is a deep-dive into the presumed origins of patriarchy and “matricultures”. And as Eisler shows above, once control becomes an organizing principle it assumes the power of a cultural norm (some of you may have seen Tema Okun’s brilliant piece on the attributes of “white supremacy culture” and will notice many parallels).

2. Patriarchy is an ideology: it presents itself as natural and therefore unquestioned.

Donna Pendergast and Sue L.T. McGregor write:

Patriarchy is an ideology—an unquestioned set of values and beliefs held by a social group… [It] has become so ordinary that it is largely invisible or assumed.

At its crudest, this ideology takes the form of “might makes right.” In practice, we invent stories to justify what on its face seems morally indefensible: a system enforced through domination that arbitrarily elevates one group of people over another. Just as the system of slavery depended on pseudo-science (craniometry) and myths (happy darky) to dehumanize enslaved people, so too does patriarchy seek to justify its legitimacy. As Tyrion Lannister said in the Game of Thrones: “It's easy to confuse what is with what ought to be, especially when what is has worked out in your favor.”

The pseudo-scholar Jordan Peterson is the best contemporary example of this: he argues that hierarchies occur organically in nature, and that patriarchy is a natural expression of our propensity for structure and order. But the argument goes even farther. All of our major organized religions are deeply patriarchal, and present this hierarchy as not only logical but as morally good (God made MAN, and then woman) and it is only right and just that men are in charge. (Though I do have to flag news out just last month where a major Lutheran denomination voted in assembly to declare patriarchy and sexism sins… so the tide may be turning!)

It is vitally important to take this argument seriously, because it is the primary defense of the system and a slippery slope to enabling a culture of violence (I’m just defending order!). Peterson has millions of followers and his ideas have found resonance among Men’s Rights Activists (MRAs) and “incels” (internet slang for involuntary celibates, usually male). There’s a whole corner of the dark web that I won’t get into here and honestly can’t recommend, but it’s fundamental to understanding the surge in male violence targeting women. Natalie Wynn (via her YouTube personality Contrapoints) has the best take-down of Peterson’s fallacies, and does so with piercing intellect and good humor.

The key data point here is that it wasn’t always thus. Patriarchy is an ideology. Like all ideologies, it seeks to make sense of reality, but is not itself reality. Bobbie Harro offers a nice graphic to explain how this process of socialization works in practice:

Patriarchy was made, and can be unmade. Many of us assume that this is just the way it has always been: might makes right, the powerful prey on the powerless. Like Tyrion in this clip from Game of Thrones (disclosure: I’m with Varys on this one, albeit not with his overweening faith in one hero—or heroine—to save us all).

This was for me the particular delight of first discovering Riane Eisler’s work (and since a whole body of scholarship challenging the “conventional wisdom”). Of course it is difficult to sift the historical record for conclusive data. But at the very least we have to acknowledge that we really don’t know: the best available evidence seems to suggest an evolution toward patriarchal systems from what Humberto Maturana and Gerda Verden-Zoller call “matristic” societies that were broadly characterized by more egalitarian gender dynamics and a stronger orientation toward partnership rather than domination. I found this deep-dive into evolutionary biology and anthropology from Camilla Power a provocative and insightful exploration into our egalitarian origins, for but one compelling example.

I remember listening to this otherwise outstanding Ezra Klein episode featuring Amy Chua where they cite the famous 1954 “Robber’s Cave” study about groups of 12-year-old boys ostensibly looking at our “natural” propensity toward “us vs them” tribalism and intergroup conflict. They agreed with the researchers: yeah, we must be hardwired for this. With NO discussion of gender, or how patriarchy operates (is there any group in society more prone to patriarchy’s influence than 12-year-old boys?!). Here’s a passage from another review of the study:

The boys assembled themselves into hierarchies through taunting and insulting each other over any perceived weakness. Where each boy ranked socially was a measure of how “tough” he was perceived to be. Competition in the social order dominated everything, for example causing boys who had injuries to disguise them rather than seek medical care. Boys who seemed weak were showered with verbal and physical abuse.

To return to our first definition, this is part of the way patriarchy operates: we see a textbook example of it in front of our faces, and instead reach conclusions about our propensity for “us vs them” behavior. Another example from recent news: a study that purports to be a comprehensive look at the common features underlying mass shootings… with ZERO mention of gender or the fact that nearly all mass shooters are male. We can’t see the forest for the trees. I will say more about this in the next post on how we’re socialized into patriarchy and how it operates.

3. Patriarchy has no gender: we are all complicit in upholding the system.

I find this last point is often the hardest to grasp for those of us who have been taught to conflate patriarchy with sexism or misogyny… which are both focused on women. Sexism is prejudice and discrimination; misogyny is that plus animus (Kate Manne calls misogyny the “law enforcement branch of patriarchy”).

But it follows the first point above: patriarchy is a system (it is not about individuals) that begets sexism and misogyny, just as white supremacy is a system that begets racism and xenophobia. As John Bradshaw writes:

Patriarchy is not just about male domination. Patriarchal rules can be administered by women. Many women raised in patriarchal families are as controlling and repressive as their male models.

Here’s bell hooks:

We need to highlight the role women play in perpetuating and sustaining patriarchal culture so that we will recognize patriarchy as a system women and men support equally, even if men receive more rewards from that system.

And Miki Kashtan:

All of us, men and women, have been trained into patriarchy, and all of us pass it on from generation to generation.

If you’re like most people (including me before I embarked on this journey!), you probably haven’t read any serious feminist works by men—most of us can’t even name a single male feminist intellectual. [If you’re interested, Rob Okun’s Voice Male is a great place to start.] It’s only in the last few years that the first academic “masculinity studies” departments have emerged, decades after women’s studies departments first flourished. (The gender studies courses I took in college tended to equate “gender” with “women”). So it’s not surprising that this line of inquiry can seem counterintuitive at first blush. The key insight is this:

I had to reread that line several times, slowly, when I first encountered it.

We will return to hooks’ point about men and women “supporting” patriarchy in a future post, since on its face it also seems counterintuitive (it’s one thing to suggest that men suffer under patriarchy, but quite another to suggest that women actively support it). I will also expand more on how patriarchy harms men (and women, and nonbinary people) in Part 2 of this series.

An important note here: it is a deliberate artifact of patriarchy that we think of gender in binary terms. The artificial split between masculine and feminine (distinct from the biological difference between male and female) is what Diane Musho Hamilton has called “the most fundamental duality.” As McGregor and Pendergast note: “A distinguishing feature of patriarchy is that it creates dualisms about every aspect of the world.”

Gender (a social construct informed by but distinct from our biological sex characteristics) is and ought to be fully reflective of the diversity of human experience. Gender, like people, cannot be reduced to simple binaries (indeed, even Jewish scripture recognizes at least six different genders). I will speak primarily of men/male/masculine and women/female/feminine in these posts because that is the rigid patriarchy we all grew up in. The contemporary trans movement invites us to contemplate a broader vision of gender identity, expression, and sexuality, and is in my view a key pillar of our effort to dismantle patriarchy. Julia Serano is consistently among the most incisive trans writers/scholars I’ve encountered on these subjects.

Indeed, the emergence of the trans movement has been a powerful force in rebutting the false assumption that patriarchy is simply about men oppressing women. Because of course the patriarchy oppresses trans people most of all. Trans women in particular (and especially trans women of color) suffer sexual and physical violence at the highest levels. And while it is nearly always men committing this misogynistic violence, cisgender women are complicit in this oppression.

II. PATRIARCHY IS INEXTRICABLY CONNECTED TO ALL OTHER FORMS OF OPPRESSION… AND IT IS ALSO FOUNDATIONAL TO THEM.

There are two seemingly contradictory points here that need to be unpacked.

First, the popular discourse around intersectionality—a term coined by Kimberle Crenshaw to describe how our multiple identities (black, female, queer, etc.) influence our lived experience—offers us a useful way to move beyond the unproductive conversations about which axis of oppression is primary: gender, race, class, sexuality, etc. A long line of feminist thinkers have reached the same conclusion: the women of the Combahee River Collective noted that “the systems of oppression are interlocking.” South African human rights activist Pregs Govender made this point at the 2008 AWID forum, observing:

Second, though it is unproductive to debate primacy in the current context, it is important to understand the foundational role patriarchy played in how these interlocking systems came to be... in order to understand how to dismantle them. bell hooks famously characterized the United States as an “imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy.”*

*[Note: if you’ve never heard this term, take a deep breath and go with it. Particularly for white people, we have been taught a particular narrative about our country and its founding that makes a statement like this a bitter pill to swallow. I remember when I first encountered it I blushed at the boldness of the statement, and immediately went into defense mode, coming up with arguments about intent vs impact, relative arguments about the American imperial footprint vs colonial powers like England, all the good we’ve done, etc. My conclusion after several years of exploration: hooks’ analysis is a factually accurate description of America. It behooves each of us to do our own work to reckon with her statement and reach our own conclusions, from a place of curiosity and open-mindedness. hooks herself offers a provocative response to our instinctual defensiveness.]

She did this for two reasons: first, per the first point above, to emphasize the interlocking systems. But her word choice was also deliberate: patriarchy is the noun—the original feature—that the other adjectives modify. From a historical origin standpoint: patriarchy as a system is roughly 8,000-10,000 years old (and evidence is persuasive that it was patriarchy that led to imperialist/conquest cultures and its more modern incarnations in colonialism; Miki Kashtan does an exceptional job synthesizing various data points on this). The concept of race as currently understood is less than 500 years old (Ibram Kendi’s book on this is a masterwork). Capitalism properly understood is only about 300 years old. Thus patriarchy serves as the foundation upon which the other systems have been built, and hooks’ framing follows roughly the order in which these other systems emerged.

The practical implications of this for how we combat the imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy will be explored in more detail in my fourth post in this series on how we dismantle patriarchy. Suffice to say for now that all of our efforts need to account for the intersection of these systems (a race analysis is incomplete without gender, just as a gender analysis is incomplete without understanding the impacts of settler colonialism). One of the most mind-bending explorations of this for me was the delightfully provocative episode on “Decolonizing Sex” featuring Kim Tallbear from the All My Relations podcast.

CONCLUSION

I know that’s a lot to throw out there… and this just the opening salvo. It’s taken me several years just to get this far, and I feel like each new day I find some new insight that continues to shape my thinking (as indeed I have just in writing this post).

In my next post I will elaborate on the social mechanisms that enforce patriarchy and how our children are socialized into it… and the harm it does to us. But I’ll close for now with three quotes that capture for me the essence of this post and why this work is so difficult… and so important.

From Pregs Govender:

Patriarchy permeates our bodies. It permeates our minds, our hearts. It eats into our souls, and it divides us from ourselves and from each other. The patriarchal power of hate and fear and greed is not just something we are fighting outside of us, but something that is within us.

Viewing the challenge in this light, for me, gives new meaning to this provocative challenge from Audre Lorde.

And we’ll give Toni Morrison the last word. May she rest in peace, with profound gratitude for the gift of her words, her imagination, and her moral clarity.