A common thread in my writings is trying to define what it means to be in “right relationship.” Often this question centers on the role of the individual in the context of the collective: “I” with respect to “We.” But I’ve come to believe that inquiry is actually a reflection — a fractal — of a bigger unresolved question: what is the proper role of homo sapiens as a species — who are we? — in the context of the world?

This is not idle philosophizing: I believe this species-wide identity crisis underpins much of the polarization, dehumanization, and violence of this era. Many of us now rightly reject the mindset that has brought us to the brink of climate collapse, the notion of “dominion” enshrined in the Christian and Hebrew bible:

God blessed them and said to them, “Be fruitful and multiply; fill the earth and subdue it; have dominion over the fish of the sea, over the birds of the air, and over every living thing that moves on the earth.” (Genesis 1:26-28)

So if not dominion… what then? The opposite of domination is submission; there is a strand of thought (which in my view trends toward nihilism and eco-fascism) that sees humans as a disease, a parasite to be eliminated from the earth: this implies our proper role is submission to the point of extinction. I think that view is also dangerously misguided: we are part of nature. We belong here. The question is not whether to rule or be ruled, to dominate or be eliminated… it’s how to exist in right relationship. That is the question I want to explore in today’s post.

TL;DR: The world is reminding us that we are not in control; surviving this era of polycrisis requires that we find a way to live in right relationship with the planet on which we depend. This means a move from an egocentric view of life to an eco-centric view: this is the shift from the Anthropocene to the Symbiocene. There is a role for human agency in navigating this transformation: we are stewards, belonging to nature and responsible for nurturing the conditions for life to thrive. It is our individual and collective responsibility to identify, cultivate, and share our deepest gifts, to ask ourselves: what can I actually do to make my life of greatest use to all life?

Letting go of the illusion of control

Many of us have come to recognize — not always at a conscious level — that the old story no longer serves. We sense somehow that dominion — with its connotations of domination — has led us astray. Andru Okun explains:

Settler colonialists’ failure to understand the interrelationships between plants, animals and people set us on our current course.

Aurelie Salvaire defines the stakes:

We’re reaching the limit of the domination model… it’s threatening the whole of humankind.

As wildfire smoke again blankets the West amid a re-intensifying global pandemic, many of us share this feeling that somehow we are stuck in the “wrong story.” Getting the story right matters. Salvaire again:

If you want to change the world, you have to change the stories.

But who are we if not rulers, if not the chosen ones standing in dominion over nature? I often find myself returning to this quote from James Baldwin that feels so resonant to this moment:

Any real change implies the breakup of the world as one has always known it, the loss of all that gave one an identity, the end of safety. And at such a moment, unable to see and not daring to imagine what the future will now bring forth, one clings to what one knew, or dreamed that one possessed.

We are being asked — nay, the world is insisting, whether or not we consent — that we let go of our illusion of control, that we find a role in the world that returns us to right relationship with nature and complexity.

There are two primary responses to this requirement. The first is a desperate — and doomed to fail — effort to re-assert control; this is most visible through the rise of patriarchal revanchist authoritarianism (a predominantly right-wing phenomenon: Trump, Orban, Bolsonaro, Modi, Erdogan, etc.), but also through the rise of techno-utopians who believe that the “right” technologies can preserve our way of life in the face of tremendous change (a predominantly left-wing phenomenon: Gates, Bezos, Musk, Branson, etc.). The common feature uniting these movements: they are overwhelmingly male.

The other response is to let go of the need for control (acknowledging the fact that it was always an illusion anyway), and to focus instead on resilience, adaptation, and community… what has been called a “just transition” from a world and a story which no longer serves. Perhaps it’s not surprising that those leading social movements advocating for different ways of being are overwhelmingly female (Black Lives Matter, MeToo, Sunrise, to name just a few that started in the U.S.) Otto Scharmer, a systems-change practitioner commented on this trend in founding his organization Theory U:

Theory U is really an articulation of the more feminine side of leadership, which is largely missing in our institutions and culture today. In China we would say the yin and yang, and it’s the yin side that’s missing. Of course it’s not that we only need one or the other. It’s really about rebalancing, because right now we have too much of one and too little of the other. Rebalancing means paying a lot more attention to the cultivation of these aspects of feminine leadership, particularly as it relates to collective leadership capacity.

These are the stakes. I believe this question sits at the heart of the current rise of authoritarianism; our ability to stem that tide and navigate a just transition depends on finding a new and better story, one in which people (and men in particular) can see themselves.

From ego to eco

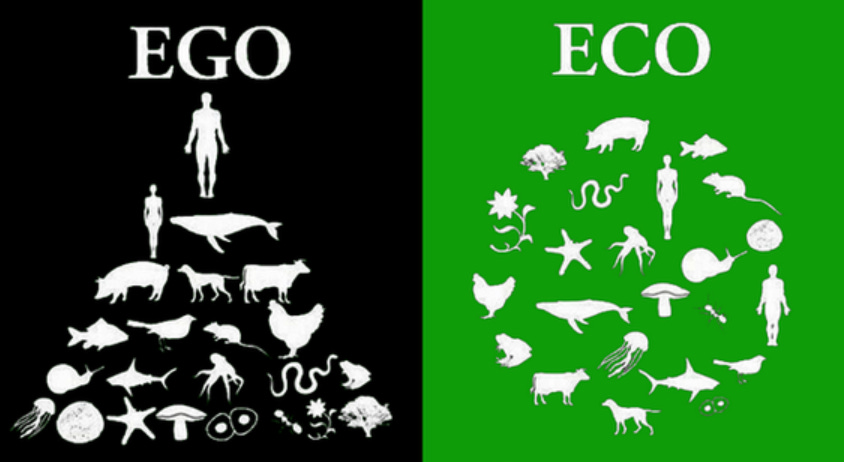

This feels like an important foundational step: re-centering our understanding of our role from an individual-centric view (a species-centric view) to situating ourselves in the broader ecosystem of which we are a part. There’s a handy graphic going around that makes this point nicely:

Robin Wall Kimmerer reminds us that this understanding has always been core to indigenous worldviews:

Indigenous ways of understanding recognize the personhood of all beings as equally important, not in a hierarchy but a circle.

I particularly love Movement Generation’s work on “eco-means-home” (the etymology for “eco” comes from the Greek word for “home”). Thus we can understand ecology as knowledge of home; economy as management of home; and ecosystem as home for the whole. We are interested in where these terms intersect, and in particular the last term: what is the role of homo sapiens in the ecosystem, in making a home for the whole?

Scharmer’s Theory U is framed around this ego-to-eco shift. While I love Theory U, the framing for me still feels too bounded by the polarity, by yin and yang, Eros and Logos, feminine and masculine… it still feels limited by those categories. I yearn for something more than a re-balancing; I want a new way of relating that transcends those categories entirely.

From the Anthropocene to the Symbiocene

My favorite framing of this shift that I’ve found so far comes from this magnificent essay by Glenn Albrecht that introduced me to the neologism “symbiocene,” his own coinage (hat-tip to Building Belonging member Gail Davidson for pointing me to it!). It takes ego to eco from the individual/species perspective to the global ecosystem perspective. The Anthropocene describes the current geologic era, defined as “the period during which human activity has been the dominant influence on climate and the environment.” Whoops! A pretty clear sign that we’re not in right relationship: dominion taken to its (il)logical extreme. This is embodied perhaps most clearly in the concept of “planetary boundaries overshoot” so brutally documented in the latest IPCC report.

So what’s next? In describing his vision for the Symbiocene, Albrecht explains the purpose and parameters:

In the Symbiocene, human action, culture, and enterprise will be exemplified by those cumulative types of relationships and attributes nurtured by humans that enhance mutual interdependence and mutual benefit for all living beings (which is desirable), all species (essential), and the health of all ecosystems (mandatory).

That feels right to me. Daniel Schmachtenberger calls this being omni-considerate… perhaps a capacity available only to homo sapiens (with appropriate humility about the consequences of interventions in a complex system). Albrecht continues:

Ecosystem parameters can be guided by key ecological players in the system to maximize benefits for the life-chances of whole species.

Within bounded ecosystems (a marsh, a jungle, a prairie, a lake) there are already “keystone species” or “ecosystem engineers” who play this role: the beaver is the paradigmatic example on land, as kelp is for the shallow seas. But humans are the only species I’m aware of that hold the potential to play that role across ecosystems: to think about and act on the relationship between the Amazon rainforest and the Arctic tundra.

So what might that role look like?

Rewilding, stewarding… and beyond

I’ve been looking for the noun that describes our species identity, or the adjective that describes our role: how can we be in right relationship if we don’t know our role, our higher purpose? Put a different way: we are interested in transformation at global scale. That is what the shift from Anthopocene to Symbiocene requires. What is the human role in that transformation?

Among people committed to a world where everyone belongs, there are two different approaches that I find myself wanting to integrate, or transcend. British environmentalist George Monbiot has been a leading proponent of the concept of “rewilding.” After some initial restoration/repair work, he explains:

I see humans having very little continuing management role in the ecosystem. Having brought back the elements which can restore that dynamism, we then step back and stop trying to interfere.

Indigenous scholar Tyson Yunkaporta, by contrast, describes humans as a “custodial species.” He explains:

Why are we here? It’s easy. This is why we’re here. We look after things on the earth and in the sky and the places in between.

“Rewilding” feels too passive to me: it is rightly skeptical of the colonial impulse for control and scale… but in my view falls short of allowing the full expression of humanity’s gifts. It still sees us as somehow separate from nature, by removing ourselves from it… it denies our agency.

“Custodian” feels like it’s more in the ballpark: I’ve long resonated with the notion of taking responsibility for the whole, and preserving a role for human agency in that ethos. As Gibran Rivera said:

You don’t plan emergence, you create the conditions for emergence.

Yet… I don’t think it’s as easy as Yunkaporta would have it. Something about the connotation of “custodian” still doesn’t feel quite right. Paradoxically, it has the same effect of removing humans from nature, of exceptionalizing us in some way: nature as something we have “custody” over… feels uncomfortably close to dominion. I know this isn’t how Yunkaporta intends it, but I think the inquiry is more than semantic (witness the “guardian vs warrior” debate in the context of policing). Words matter: they shape identities, and therefore behavior.

I suspect this is a failure of language, or at least of English (language of the colonizers…). “Stewardship” is the closest I’ve found, another term that emerges in indigenous worldviews… I like its etymology of “keeper of the home.” Plus, the literature is very clear that indigenous stewardship of land contributes to far better biodiversity and overall outcomes than nature-without-humans. This is the shift from restoration (rewilding) to emergence (stewarding?); Alex Evans had a great thread on this distinction in the context of Monbiot’s work.

Can we cultivate an ethos of stewardship that situates us as actors within the ecosystem we steward… belonging to it?

Not exceptional… but unique

There is a unique role for us. I don’t think we are superior to or better than other non-human beings. We can’t photosynthesize. We’ve only been around a few hundred thousand years, living among species that trace back millions. This is not about setting ourselves “over” other beings. But nor is it about denying our unique gifts, or the responsibility that flows from those gifts. As far as I know, there are no other species that can communicate instantaneously across the whole world, for example. Yunkaporta explains:

Our minds are such that we’re able to perceive the entire system… We can perceive an entire complex system, but we can also perceive the systems beyond that system and the way they interact.

I think that’s right, and I think with that unique gift comes a responsibility to act accordingly. I guess what I’m resisting is the notion that we’re acting on behalf of someone or something else without being honest about the fact that we belong to it. We are part of nature, we of course have a stake. The traditional connotation of stewards, guardians, and custodians… are generally not “of” the thing they are stewarding. They don’t belong in some meaningful sense. I want stewardship AND belonging.

I think maybe the bridge I’m looking for is captured in the idea/act of “nurturance culture,” a concept beautifully expressed by Naava Smolash (nom de plume Nora Samaran). It carries the connotation of rematriation (the masculine-to-feminine, ego to eco shift Scharmer identified), and contains within it an element of reciprocity that feels missing from the steward/custodian language: it locates us IN nature, rather than just somehow guiding it. Nurturance is by definition mutual: you cannot give a hug without receiving one. I’ve become increasingly interested in the metaphor of seeds to illustrate this idea: the seed itself is the fractal, the encoded gift of millennia of evolutionary knowledge. Left to its own devices (rewilding) it will likely grow. But it may not: there is a role for humans as stewards, as gardeners, to nurture the conditions for emergence, for life to thrive.

At the risk of over-cluttering the tapestry I’m trying to weave with this post… I want to bring in one more thread here.

From self-actualization… to cultural perpetuity?

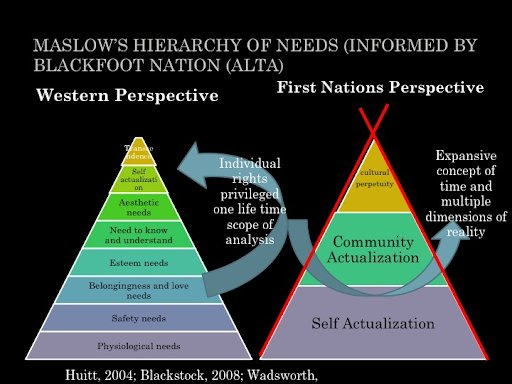

I loved this recent post from Teju Ravilochan, building on Cindy Blackstock’s work revisiting Maslow’s famous hierarchy of needs. In it he explores an indigenous worldview through the lens of the Blackfoot people, wherein the highest aspiration is not self-actualization but rather what Blackstock calls “cultural perpetuity.”

I really like that framing. The inquiry it connects with for me: what is our highest purpose? As individuals… and a species? I’ve long rejected the binary: the always-mythical “rugged individualism” of America and some Western cultures on the one hand, or the flattening/homogenizing collectivism of some Eastern or indigenous cultures on the other. Instead of competition vs collaboration… both/and? There is an assumption that individualism is necessary for innovation. While I’ve witnessed the undermining of individual initiative firsthand in my travels in more collectivist cultures (the Central African Republic in particular), I don’t think it has to be that way.

I’ve long been searching for the “right” place for competition. I love competition, primarily through sports: both individually, but especially as a team. It’s always been clear to me that team sports are way harder to excel at: they require more than individual achievement. I compete not to win, not to dominate my “opponent,” but to be my best self… always understood in relationship to the team, and our shared desire for us to be our best team. That elusive energy I’m always seeking: when I’m at my best in symbiotic relationship to what is best for the team. Pushing myself, ourselves, to the absolute limits of our individual and collective capacity… always seeing if there is more potential to be reached. This is the beauty of emergence: collective outcomes are possible which exceed the aggregate of the individuals involved.

I finally found a definition I resonate with, from the “regenerative development” literature:

A competitive striving for excellence taking place on a fair playing field within an overarching cooperative context.

Yes, that feels right. adrienne maree brown (channeling rapper Drake) talks about “working on excellence.” Yes, but to what end? For whom?

Life’s longing for itself: becoming?

The Blackfoot model I think offers a helpful way to think about it. The thread I’m trying to weave here: there is something about coming fully into our individual gifts, in order to fully actualize our collective potential (as a society, as a species) in order to fully actualize our proper role in the broader ecosystem. Here’s how Teju translates the Blackfoot worldview:

We are each born into the world as a spark of divinity, with a great purpose embedded in us. That means that we arrive on earth self-actualized. (emphasis in original)

This feels right to me: the task of each individual is to become ever-more-fully oneself, to discover, cultivate, and honor that deepest gift that is unique to each individual. Then: to offer that gift in its fullness to the collective. Self-actualization as a necessary condition of societal actualization. This is why I find the I, We, World framework so powerful: it is a fractal relationship. For us to fulfill our proper role as individuals, societies, and species, each dimension/scale is interdependent with the others.

And of course the goal of all this: life itself. Life creates conditions for life to thrive… what Kahlil Gibran evocatively called “life’s longing for itself.” In a previous post I quoted David Graeber here, because it’s the closest I’ve come to finding this idea expressed:

To exercise one’s capacities to their fullest extent is to take pleasure in one’s own existence, and with sociable creatures, such pleasures are proportionally magnified when performed in company.

I think he’s got the first part right. I would amend the second: it’s not about being in company, it’s about being in relationship, doing something together. It’s about exercising one’s capacities to their fullest extent… alongside others doing the same, in pursuit of a shared goal. Cindy Blackstock’s Gitksan people have another term for “cultural perpetuity”; they call it simply “the breath of life.”

This is the world I want: where each of us (individually, and as species) are doing what is best for us… which is also best for the whole. We already have a model for this: the human body. Daniel Schmachtenberger explains:

It is how your body works, where none of the cells are advantaging themselves at the expense of the others. They’re doing what’s best for them, what’s best for the whole symbiotically at the same time… there is no definition of success for ourselves that is not a definition of success for everything.

This is what it means to live in the Symbiocene, to actualize ourselves and the collective and the world… at the same time. Cameroonian public intellectual Achille Mbembe, in a wonderfully vast reflection on the “planetary,” offers this:

We, the humans, coevolve with the biosphere, depend on it, are defined with and through it and owe each other a debt of responsibility and care.

As indigenous seed-keeper Rowen White puts it:

We have to be good future ancestors and responsible descendants, so it’s our responsibility to care.

This is the question Schmachtenberger poses, which I find infinitely fascinating; this is the vision of “working on excellence” that I think we as individuals and a species can aspire to… another version of asking “what is my (our) unique gift?”:

What can I actually do to make my life of greatest use to all life?

I once again deluded myself into thinking this would be a quick-and-easy post to set up the next one. I’m intentionally writing this following my reflections on the gift economy… and before taking on the question of global scale (next post). Both of these questions to me turn on how we understand our unique role as a species, and therefore how we organize ourselves in relationship to the land and other beings with whom we are in reciprocal interdependent relationship.

I know I’m not alone in thinking seriously about this question, though I worry it may seem too immaterial for many of my readers in the context of the crises we now face. Obviously I think this matters: I think getting this question “right” informs how we approach everything… but I’d love to hear what resonates, what doesn’t, and how you’re making sense of what this world — and this moment — is asking of us.

Love all of this. It's anything but immaterial; it's vital. The Baldwin quote articulates some wonderings I've had over the past couple weeks, and all the ground you cover here resonates wonderfully. This line of your own in particular: "I want stewardship AND belonging." (Robin Wall Kimmerer's word is "kinship.")