Here in Seattle, ground zero for the U.S. COVID-19 outbreak, we’re now entering month two of a changed world. A world where two things are true at the same time: we are all in this together; and the way the virus impacts us magnifies and exploits the fissures running through our deeply divided societies.

Watching the sad spectacle of states and countries competing with each other for personal protective equipment and ventilators I was reminded of a brutal line in John Washington’s essay on open borders:

Borders function as moral shields—the limits to which citizens are willing to extend their empathy.

I launched this newsletter a year ago with a rumination on this question: can we create an ‘us’ without a ‘them’? The coronavirus makes this challenge more acute: can we expand our conception of who and what we care about? As Hala Alyan put it in a beautiful reflection for Emergence Magazine:

This pandemic seems to have at its core a lesson of kinship. What do we owe each other?

I want to use this post to explore a theme that I’ve been circling around for my entire life: what Vaclav Havel memorably called “responsibility for the whole.”

TL;DR: We are in an unprecedented moment where the whole world is living through (albeit in very different ways, along lines demarcated by interacting systems of oppression) a shared experience. It emphasizes our fundamental interconnectedness, and presents for each of us an opportunity to act on that undeniable fact: to take responsibility for the whole.

I, We, World

One way I’m responding to this moment: I’m co-curating a set of online convenings in the coming months organized around the art of transformation: at an individual (I), societal (We), and systems (World) level. Another way of framing the inquiry: what are the necessary and sufficient conditions to enable this new world to emerge? To enable global transformation?

It’s become increasingly clear to me that individual change, societal change, and global systems change are deeply interrelated. But the art of change or transformation is so often conceived and practiced in the same silos that keep us divided: mindfulness over here, conflict mediation over there, systems change and emergence in still a third place.

When I left the Gates Foundation four years ago I was looking for a unifying thread to tie these strands together. I found that thread (at least for me!) in the concept of belonging, beautifully expressed here by the inimitable Grace Lee Boggs.

Taking responsibility for the whole

Belonging to the world… and responsible for it. I’m reminded of a line from Jane Nelsen — the parenting guru who founded the “positive discipline” movement — who observed (channeling psychologist Alfred Adler):

A sense of belonging without contribution equals a feeling of entitlement.

Yes. Significance and belonging = responsibility. This is what we need to cultivate. Vaclav Havel delivered one of my favorite speeches of all time on this subject, for Harvard commencement in 1995. The whole thing is worth the read, but here’s the thesis:

The main task in the coming era is… a radical renewal of our sense of responsibility… for ourselves and for the world.

john a. powell talks about this as “expanding the circle of human concern,” and it feels to me like the most pressing mindset shift of this moment. What if we didn’t let arbitrary geopolitical borders or blood relations set limits on our sense of human connection and moral responsibility?

This pandemic invites us into those questions in a visceral and universal way: yes we miss our families… and we miss our friends. We miss the spontaneity of interactions with strangers, the fundamental need that is connecting with another human being.

My favorite book of 2019 was Nora Samaran’s brilliant and deeply nuanced The Emergence of Nurturance Culture, where she concludes:

The idea that we have relational responsibility only to those humans we love, and no responsibility toward anyone else, is destroying the very fabric of human connection in Western societies.

(This morning NPR reported that the suicide rate in America has risen yet again, increasing year-over-year for over 20 years).

This is about reconnecting with the feminine

My readers will know that I reject the arbitrary division of universal human attributes into the false binary of “masculine” and “feminine.” Yet this is what patriarchy does. The transition we are being asked to make (before COVID, but now urgently because of COVID): from I to We, from competition to cooperation, from domination to partnership… is a transition from stereotypically masculine attributes to more feminine attributes.

So it should come as no surprise that those leading in this moment of transition are overwhelmingly female. Our new definition of “essential worker” is a category overwhelmingly led by women, particularly in the caring professions (eldercare and hospice, childcare, public health professionals, especially in nursing), but also in cleaning and domestic work, food preparation, etc.

It has also been my consistent experience that those leading the planning for the future (the world that awaits us when we emerge from our collective chrysalis) are overwhelmingly female. I have the privilege of participating in a broad range of very diverse spaces around building this new world (e.g. a global call featuring over 10,000 people hosted by Otto Scharmer’s Presencing Institute on the “gaia journey”; a virtual practice for nearly 400 people on “purposeful resilience in uncertain times” led by the Strozzi Institute’s Staci Haines; an interactive dialogue with about 80 people hosted by Gibran Rivera on Adaptive Change). The common feature? Women made up 70-90% of the participants in each.

Our definition of leadership needs to change. Nipun Mehta talks of moving from “plan and implement” to “search out and amplify.” Frederic Laloux talks of moving from “predict and control” to “sense and respond.” Miki Kashtan, one of my favorite writers and practitioners, described a set of shifts that need to happen, concluding that “care for the whole” is the defining feature of “feminist leadership.” It comes as no surprise that those “leaders” most wedded to the swaggering paradigm of dominant masculine leadership have been least prepared and least effective in the COVID response: Johnson, Trump, Orban, and Bolsonaro. And perhaps not surprising that the most effective leaders thus far: Jacinda Ardern and Angela Merkel.

Care connects us all

It’s no accident that we talk about Mother Earth, or that our conceptions of Gaia or one-ness always invoke some notion of the sacred feminine. I was listening to a beautiful podcast interview yesterday featuring Krista Tippett in dialogue with Ai-jen Poo, where Ai-jen had this great line: “care connects us all.”

We have an opportunity now to practice that connection. In a conversation taking place BEFORE the coronavirus hit, Ai-jen is prescient:

This is a once-in-several-generations opportunity to transform and update how we care for one another.

This is both simple and complicated, particularly in our gendered society. It has always been true that we must first be cared for in order to learn to care for others. But emerging research pioneered by Alison Gopnik goes further: she contends that the very act of caring is what leads to love. In other words, we have the sequencing backwards: we don’t care because we love, we love because we care.

So it should not surprise us that women are better-prepared for this moment, and that many men are struggling. If we’re going to make it through this, we all need to build and stretch that muscle. Greg Snyder had a great reflection in a discussion with Francesca Maxime on undoing patriarchy:

How do we support people, and men… in feeling into the terror of what it would be to not be in the world in a certain way?

I’m reminded of that great line from Baldwin, which I quoted in a previous post:

Any real change implies the breakup of the world as one has always known it, the loss of all that gave one an identity, the end of safety. And at such a moment, unable to see and not daring to imagine what the future will now bring forth, one clings to what one knew, or dreamed that one possessed.

We are ready to change

Virtually every article and think-piece about coronavirus adopts a metaphor relating to transition. But there is a subtle feature to how the human brain responds to major change that prepares us not only to navigate the transition but to continue along a new path once the triggering event has passed.

This is the emerging science around neuroplasticity: the notion that our brains become uniquely amenable to “re-wiring” in the face of dramatic change. There’s growing literature around motherhood exploring this phenomenon, reinforcing my own tendency to gravitate toward birth as a metaphor for this moment (and again why women are often better prepared).

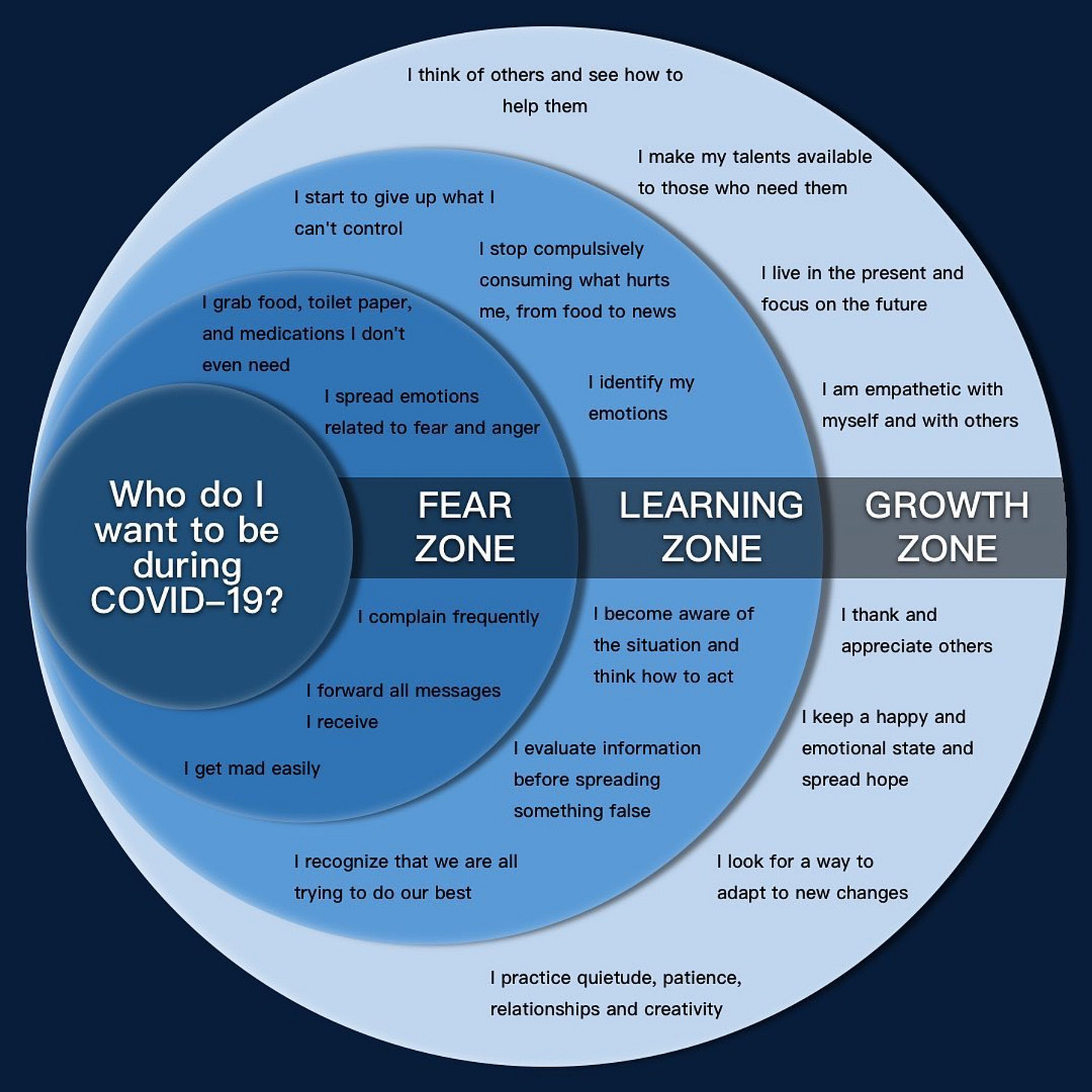

This means that the choices we make right now in how we respond to this crisis will inform how we live in the new world that is coming into being. I love this graphic (I couldn’t find original attribution), but I would reframe the prompt to simply: who do I want to be?

Let’s build new habits

Arundhati Roy, whose writing always feels like our collective conscience making itself heard, says this:

Our minds are still racing back and forth, longing for a return to “normality”, trying to stitch our future to our past and refusing to acknowledge the rupture. But the rupture exists. And in the midst of this terrible despair, it offers us a chance to rethink the doomsday machine we have built for ourselves. Nothing could be worse than a return to normality.

We can’t go back. Nor should we want to. Increasingly people are coming to recognize this essential truth. As Daniel Christian Wahl wrote:

The way to care for our selves and our families, the way to sustain this and future generations of human beings is to care for life as a whole. (emphasis in original)

Systems thinker Daniel Schmachtenberger calls this being “omni-considerate.” International conflict mediator Ken Cloke calls it being “omni-partial.” And it starts right now, with each of us. The Presencing Institute reminds us:

During this moment of global transition, it’s essential to shift personal behavior to positively shift societal outcomes: energy follows attention. (emphasis in original)

James Clear has emerged as one of my favorite practitioners on the art of forming new habits, and manifesting an identity in line with our aspirations. Psychologist Carl Rogers believed that this is the definition of self-actualization: when our ideal self is aligned with our actual behavior. Here’s Clear:

Every action you take is a vote for the type of person you wish to become.

So, here we are, in global lockdown during an election season. As we think about the kinds of politicians we want to represent us, we have a unique opportunity to act in the direction of our dreams. Who will you vote to be?