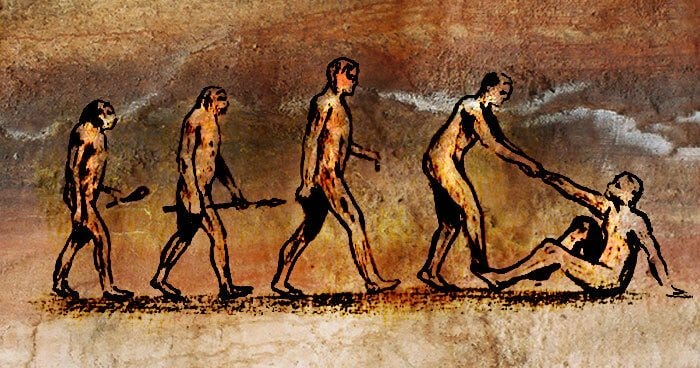

What if Darwin was wrong?

What if evolution is as much about collaboration as it is about competition?

A growing school of thought is challenging core assumptions many of us have long held about human nature. It feels simultaneously incredibly exciting, and absolutely earth-shaking.

There are two core assumptions that we seem to take for granted in every discussion about human nature:

(1) we are wired for competition, and

(2) we are wired for tribalism, toward in-group preservation and with a propensity for hostility (and even violence) toward out-groups.

Here’s the question I’d like to explore today: what if those assumptions are wrong? Or at least, only half-right?

Today’s most contentious debates are actually debates about human nature…

…but we rarely acknowledge that.

The impetus for this post came listening to a brilliant interview on Daniel Thorson’s Emerge podcast with Zak Stein. The whole thing is a mind-bending listen, but the idea that stood out to me was Stein’s point that while we tend to focus in the humanities (education, psychology, sociology, philosophy) on what a human ought to be, we rarely devote equal attention to the first-order question of what a human is. Or we actually do argue about that, but without naming it as such or even realizing that’s what we’re arguing about. He explains:

The argument about education boils down to an argument about human nature.

The implications are profound. If we think human nature is fundamentally competitive and tribal, then the point of education (and our system of government) is to restrain our baser impulses, to provide some boundaries to enable us to function as a collective. A 2017 lecture by Jonathan Haidt illustrates this line of thinking:

It is difficult for tribalistic humans to run and sustain a modern liberal society founded on compromise, toleration, and impersonal rules and institutions. Pulling it off requires getting a lot of social settings just right. Those settings include formal laws like the Constitution, informal norms like law-abidingness and truthfulness, rules-based institutions like free markets and elections, a system of education that inculcates liberal values, and public mores that honor and defend those values.

Here Haidt is making an argument about what kind of society we ought to construct, what kind of rules should govern how humans interrelate. He takes for granted his premise, namely that we are “tribalistic.”

Reports of “tribalism” have been greatly exaggerated

The argument that we are tribal (rarely framed as an argument, usually just as accepted fact), goes like this:

Humans evolved from small bands of roving hunter/gatherers (a “tribe”)

Survival and threat-detection then gave us a strong in-group bias (our tribe)

Which implies an instinctive dislike/distrust of “others” (not our tribe)

I thought a lot about this listening to an excerpt from Ezra Klein’s new book “Why We’re Polarized” on his podcast. The whole thing is an extended meditation on in-group vs out-group behavior, and why we’re so wired for ‘us vs them.’ My problem is this: we have no good way to tease out the nature vs nurture aspect. One of his major case studies revolves around 15-year-old American boys in the 1970s. I’m not disputing that the boys in his study exhibit strong ‘us vs them’ tendencies. I am disputing that we can draw any definitive conclusions about our genetic or evolutionary predispositions: the pressure of patriarchal socialization (in a “meritocratic” capitalist system) for that particular demographic is unbelievably intense.

Christine Mungai takes on this uncritical line of thinking, contending:

The current use of “tribal” is based on a racist stereotype about how groups of such peoples have interacted historically, and even today… the word “tribe” was a product of colonial logic, reserved only for people not considered fully civilized in that era.

She too examines cases where there is significant intergroup rivalry or violence (like Klein), but reaches a different conclusion:

Even if “tribal” might be synonymous with intense rivalry in such a case, that’s a result of patriarchy, not tribal identity per se.

Humans are wired for collaboration

On the one hand, this is an obvious statement: we never would have made it this far as a species if we couldn’t figure out ways to work together. Yuval Noah Harari puts it succinctly:

Evolution thus favored those capable of forming strong social ties.

New discoveries across a diverse range of fields are finding that it goes even deeper than that. This new article from John Favini is breathtaking in its implications, and a fascinating read, upending over a century of uncritical scientific consensus. We have long known that any complex ecosystem depends on an interdependent web of interaction to thrive: the gazelles eat the grass, the cheetahs eat the gazelles, etc. But that understanding is framed within the context of competition: survival of the fittest. An emerging scientific consensus starts from a different departure point:

Rather than competition, it was collaboration that constituted the origins of… all complex life on planet Earth. (emphasis in original)

The task of the human brain is to accurately move from perception to interpretation. And it turns out our interpretations are colored by our identities, cultures, biases, etc. Here’s Favini, echoing Mungai in returning to where Darwin went wrong:

Like all humans, Darwin brought culture with him wherever he traveled. His descriptions of the workings of nature bear resemblance to prevailing thinking on human society within elite, English circles at the time…. Darwin characterized the principles underlying his thinking as naught but ‘the doctrine of Malthus, applied with manifold force to the whole animal and vegetable kingdoms.’

Of course: we are products of our times, and of the identities we inhabit (at the time of Darwin’s writing, entire bodies of knowledge from virtually every indigenous community in the world held a very different — and scientists are now finding, far more accurate — understanding of the intricacies of natural relationships). Here’s the important takeaway:

We must to learn to recognize the impulse to naturalize a given human behavior as a political maneuver. Competition is not natural, or at least not more so than collaboration.

This changes everything

It is difficult to overstate how foundational this is. Our assumptions about human nature underpin… literally everything. How and why we build schools, and conceive of education. Prisons. The entire system of capitalism is predicated on our supposedly “natural” inclination and drive toward competition. Our inability thus far to meaningfully address the climate crisis hinges on this premise.

Jeremy Rifkin reached a similar conclusion in his path-breaking 2010 book on what he called “Empathic Civilization.”

Written in the aftermath of the global financial crisis and the collapse of the Copenhagen climate talks, he concluded:

The real crisis lies in the set of assumptions about human nature that governs the behavior of world leaders.

And therein lies the opportunity. Here’s John Naisbitt:

The greatest breakthroughs of the 21st-century will not occur because of technology, they will occur because of an expanding concept of what it means to be human.

Systems thinker Donella Meadows famously offered a 12-point thesis on how systems change happens, titled “leverage points in a system.”

As I’ve been thinking about my own theory of action in the world, I have found myself drawn to the highest leverage points: system goals (e.g. reframing from increasing GDP to improving human well-being); and the paradigm or mindset undergirding the system (e.g. from domination to partnership). This is the first time I’ve now understood — I think? — what she means by the highest-leverage intervention, the power to transcend paradigms entirely. She explains:

There is yet one leverage point that is even higher than changing a paradigm. That is to keep oneself unattached in the arena of paradigms, to stay flexible, to realize that NO paradigm is “true,” that every one, including the one that sweetly shapes your own worldview, is a tremendously limited understanding of an immense and amazing universe that is far beyond human comprehension.

This insight about human nature feels like one of those paradigm-transcending interventions: if we can expand our concept of what it means to be human (following Naisbitt), and stay open to the possibility of multiple truths… then every other change becomes possible.

What if being human is just the art of trying to do better?

Rethinking our understanding of human nature gives us a way forward, a path out of the doom loop of polarization, recrimination, and hostility. Jonathan Rauch has a great essay in National Affairs on “rethinking polarization,” where he starts his conclusion with this unquestioned premise:

We cannot change human nature. We are stuck with our Serengeti-evolved selves.

I think he’s partially right… but not in the way he thinks he is. We don’t need to change human nature, we need to change how we understand human nature, to recognize a fuller picture of our own complexity and our humanity.

And I think he’s wrong. We can change human nature, because part of our nature is our capacity to learn and improve… to evolve. I was listening to a beautiful interview with Alison Gopnik for Krista Tippett’s OnBeing podcast on “the evolutionary power of children,” where Gopnik concludes:

What the science tells us is that there’s this stream, this river, this ability to change in unpredictable ways. And when we see our children, we actually see that in real life, for good or for ill. But that’s what human nature is all about. Human nature is culture. What’s innate in us is our capacity to learn and change. That’s what human nature is really all about. And I think that’s a much more hopeful and positive picture than maybe some of the pictures we’ve had in the past.

A concluding thought. Jennifer (my wife) and I just finished the final episode of The Good Place, a fascinating sitcom about moral philosophy, revolving around this central question: what do we owe each other? It’s a great series, and I think they essentially get it right. It boils down to this:

1) Ultimately, we don’t know. About the afterlife, about the meaning of life, about human nature, about… anything. There is a lot of uncertainty in this messy thing that is existence.

2) Even so, we have to try. To do better, to improve, to treat each other well.

In my annual “new year’s note” this year I pointed to Anna’s inspiring song from Frozen 2 (ironically, sung by The Good Place’s Kristen Bell) that feels exactly right to this moment, and to this debate over human nature: Do The Next Right Thing. It’s about restoring agency to our actions, to saying: what I do matters. Because it does.

What we believe matters. It comes back to the parable of the two wolves that I shared in one of my first posts. We have both of these things (competition, collaboration…and more) within our selves, in our nature. Which one prevails? The one we feed.