There is a justified backlash to hierarchy: as an organizational structure, as a way of organizing society. We rightly reject it as an instantiation of injustice: privileging some over others. Yet here is my fear: in rightfully opposing domination hierarchies—which need to be dismantled—we risk losing the vital importance of developmental hierarchies… which are essential for our prospects for individual and societal transformation.

In our opposition to domination hierarchies there are two common—and in my view unhelpful—responses. One is to invert the hierarchy, changing who’s on top. No help there: I’m interested in ending oppression, not changing who’s oppressed. The other is to eradicate the hierarchy and insist on equality/horizontality. This second piece is the phenomenon I want to unpack today. In our rightful insistence that all lives have equal value—the radical truth that no one is more valuable than anyone else—we risk inadvertently flattening important differences, in ways that harm our movements for justice and liberation.

Today I want to talk about why developmental hierarchies matter, and why our movements for justice urgently need to find ways to come to terms with them, and integrate them into our work. This concept is related to the discourse around governance and organizational structure (from hierarchy to heterarchy, or sociocracy, or Holocracy, or…), but different. Today I’m focusing on the process of transformation, not the structure/container within which it occurs… though of course they’re related.

TL;DR: We need to learn to differentiate between domination hierarchies (which need to be dismantled) and developmental hierarchies… which are vital for our movements for transformation. To progress along a developmental hierarchy is to build our capacity to tolerate complexity: it is to build our capacity for transformation. The fastest path to transformation is apprenticeship: to learn from a master. This puts a premium on what Cyndi Suarez calls “curatorial leadership”: the art of identifying and convening those who have built capacity to a point of mastery. This work is essential if we are to have any hope to transform with the speed and scale this global moment requires.

Types of hierarchies: domination, nested, developmental

I want to start by distinguishing between three types of hierarchies that I fear we too often conflate. Most of us intuitively understand hierarchies as relationships of power and superiority/inferiority (etymologically, “-archy” has to do with rule/authority): these are domination hierarchies. Higher is better, lower is worse: a zero-sum mindset is assumed, and value-judgments follow. This is how our culture is structured, because domination hierarchies are the core logic of all of our underlying systems of oppression: white supremacy places white people over people of color; patriarchy elevates men over women/nonbinary folks; capitalism elevates capital/owners over labor/workers, etc.

Nested hierarchies are different: they contain no value judgments, no better/worse or superior/inferior. Rather, they describe a set of relationships, often correlated to scale. In biology this is the hierarchical logic of Kingdom-Phylum-Class-Order-Family-Genus-Species. Though this is often graphically depicted as top-down (and thus looks similar to a domination hierarchy) it’s better understood as nested or descriptive: each level corresponds to a different degree of specificity/abstraction. We understand that there is a relationship between the species Chihuahua, the family canine, the Kingdom of animal, etc… without needing to weigh these distinct categories against each other or elevate one over another.

Developmental hierarchies I think are where our movements currently struggle the most. I’ve been searching for a long time for a way to talk about this that does justice to the nuance and complexity that exists here, and haven’t really found it… but I’m determined to try, because I think the stakes are high. Gibrán Rivera had the best synopsis I’ve seen trying to draw this all-important distinction:

There is an important distinction between “domination” hierarchies and… “developmental” hierarchies. We learn things. We grow. We get better at doing the things that we practice. We go from not knowing, to novice, to apprentice, to master. This does not mean we exert dominance over anyone. But it does mean that we have ascended up a developmental hierarchy. We have learned something we did not know. We have gotten better at something. We have grown.

The most intuitive example for me is the developmental progression of different “belts” in martial arts: you start with white, and progress through a set of developmental stages until you reach black belt. And of course, you never arrive: the master is never finished, because by definition there is always a higher (deeper, farther?) degree of mastery. It is this third dimension of hierarchy I want to explore today.

Why does this matter?

It is an article of faith for me that we need to maximize collective intelligence. The challenges we face are so complex and interdependent that any prospect of resolving them will necessarily require everyone’s contributions to the best of their abilities. As Einstein reportedly noted:

We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.

Which means two things: we need to find ways to ensure that everyone’s intelligences are represented… AND we need to find ways to rapidly accelerate our individual and collective capacity for learning (and un-learning/healing). Both pieces are essential.

As a society we need to learn to recognize and celebrate diverse sources of wisdom; I like Alanna Irving’s Full Circle Leadership as one intuitive example. In the context of a patriarchal dominant culture which privileges the supposedly logical mind as the primary source of wisdom and value (homo economicus, and his apotheosis in “Davos man”), this means intentionally seeking out and elevating marginalized intelligences: the wisdom of the body and of other nonhuman beings in particular. Many indigenous cultures have deep experience in these ways of knowing.

But it is this second point I want to focus on today: how we can accelerate our individual and collective processes of transformation. If we are serious about responding to the polycrisis—and the climate crisis in particular—on a time-scale commensurate to the threat, we simply can’t afford not to.

I find it helpful to think about this in the context of the stages of racial identity development. A theory—emerging from practice—developed by Janet Helms and elaborated by others proposes a progression in racial identity formation.

Here’s the thing: while of course not all transformation is linear, there is no way to end white supremacy without individually AND collectively progressing through some version of this developmental hierarchy. We simply can’t get there without building our individual and collective capacities: we must first disintegrate before we can reintegrate. The caterpillar must go into the chrysalis to become a butterfly. There are paths that move rapidly through these phases (1-2 years, say) and paths that can take 5-10 (among people committed to the practice). And of course, no transformation is possible without practice. We urgently need to transform as rapidly as humanly possible, to create paths that put people on the fast track.

The fastest path to transformation is apprenticeship

I encountered this idea via James Clear’s book review of George Leonard’s “Mastery,” and it felt like an epiphany, giving name to a conclusion I had been reaching but not yet articulated. Clear explains, channeling Leonard:

For mastering most skills, there’s nothing better than being in the hands of a master teacher.

Two more seemingly contradictory truths to hold here: all learning is always multidirectional—as any parent can attest, we learn so much from our children—AND there is an important role for experience and expertise. There is a meaningful and important distinction between novice, apprentice, and master.

I think where we struggle is how to describe the relationship between people at different stages of a developmental hierarchy. And I think a big piece of the problem is our language: we rely on value-laden language (better/worse, e.g.) and fixate on nouns rather than verbs (identities as fixed rather than dynamic: even the language of “novice” and “master” feels artificially constraining). Diane Musho Hamilton has a great reflection on this conundrum:

People don't like stage theory and developmental models because it feels like a hierarchy where some are superior to others and looks like a dominator hierarchy. But in fact what we are saying is that there are progressive capacities to tolerate more complexity.

Here’s the relational distinction that feels liberating to me: we evaluate capacity relative to the goal, not to other people. The master is a master not because she is “better” than other people. She is a master because she has cultivated a set of practices with intentionality, and has achieved a level of mastery of those practices. She has cultivated the ability to tolerate more complexity: in an embodied way. Transformation takes place in the body; it is not solely a cognitive process. The developmental hierarchy then is not about where you are relative to other people. It’s about where you are relative to where you need to be… to become your fully embodied self. It’s about our capacity for transformation.

And: a master of one domain may be a novice or apprentice in another. Even within one domain someone may be a master of some capacities and a novice in others. For example, I’ve been prioritizing work in recent years around my own sense of erotic self-sovereignty: trying to define my own relationship to eroticism, sexuality, and desire. And in that one domain there is an infinite range of capacities (one of my favorite podcasts, Speaking of Sex, has over 400 episodes devoted just to this topic!) Meaning: capacity-building is inherently nonlinear: progress in one dimension does not imply progress in all.

Distinguishing talent, capacity, skill, practice

More nuance: it feels important to distinguish here between talent, skill, capacity, and practice. Here’s how I think about it: practice is the art of building capacity to attain and deepen a skill. Talent informs how fast we can build capacity (speed) and how far we can make it on the developmental hierarchy (distance).

To some extent I use capacity/skill interchangeably. The difference for me is skills can be attained: there is an endpoint. Capacities are infinite. For example we can define and attain the skill of being able to drive a car (a category which equates my abilities with those of a Formula 1 racecar driver) while distinguishing within that skill an infinite range of capacities (which recognizes that the Formula 1 driver has far more capacity). In general I think it’s more helpful to think about building capacity rather than building skills, though skills are important to benchmark progress.

Two things are true at the same time: we are capable of transformation, and our capacity to change is informed/constrained by nature and nurture. I think of talent as the most fixed element of this: it’s that unique combination of nature/nurture that sets the bar both for speed and distance. We have to be able to acknowledge that we embark on our journeys from different places with different existing capacities… without falling into the trap of implying that therefore one person is better/more valuable than another. It was this nuance I tried to explore with the concept of “prismatic leadership”: it’s available to everyone… and of course we’re all unique.

It’s easiest to understand in physical terms. In the developmental hierarchy that is playing basketball, LeBron James will be able to build capacity (the speed of development) much more quickly and will be able to go farther (distance) on the developmental hierarchy than most of us, as a function of his talent (primarily nature) and personality/disposition (nature and nurture, a response to his environment). His extraordinary capacities, however, do not constrain our capacities: they just enable him to go farther/faster. Capacity development is non-rivalrous and abundant.

One final paradox to hold here: there is no capacity development (cultivating a skill) without practice (in relationship, the purpose of which is to integrate the capacity in our bodies)… AND there is not a linear relationship between practice and building capacity. Someone with more talent might build more capacity through ten hours of violin practice than I can build in 100 hours.

We need to practice “curatorial leadership”

If the fastest path to transformation is apprenticeship, then a key task is identifying those “masters” who we want to apprentice under. Here I’ve been influenced by Cyndi Suarez’ work, and in particular the concept she has called “curatorial leadership”: it requires the capacity to… assess capacity, and delineate among different degrees of complexity. And to identify where people are in relation to different developmental hierarchies: to seek out and learn from those who have reached mastery, and who continue to push their practice. It is the art of discernment. As Cyndi notes:

We have a responsibility to ourselves to develop.

Without language to describe aspirational developmental hierarchies, we can’t develop the necessary leadership capacities to navigate and respond to this moment. We want our movements to be “leaderful”: what kind of leaders? What kinds of capacities? Who decides? How do we build those capacities? If we don’t have the language (or willingness) to distinguish between novice, apprentice, and master… who do we learn from? Cyndi’s work—and this conversation she convened in particular—is in my view a great example of curatorial leadership in action, and of exploring this topic with the nuance it demands.

My own struggle trying to practice the art of curatorial leadership—without language for it—has been to distinguish between two equally vital forms. The first is to bring masters together to deepen/expand their practice. While of course the black belt can learn from the white belt, the black belt stands to learn far more from another black belt. It was this insight that formed the basis for the Conversations on Transformation series I curated via Building Belonging. I think of this as co-defining the state of the art: assessing the limits of our collective capacities, in order to determine the direction we need to grow.

The second aspect of curatorial leadership is co-defining the path to transformation. If the state-of-the-art sets the bar for mastery—it is the goal we are trying to attain—how do we get there, as quickly as possible? Not all masters are great teachers. Not all paths are equally accessible to all people. How do we develop a variety of pathways to transformation, that can meet everyone where they are? This to me is the primary work of Building Belonging.

To me the act of curation needs to be a collective enterprise: curatorial leadership done well is co-curation, collectively determining and assessing the capacities we need for transformation, and locating them where they already exist in the world.

To me these are the necessary preconditions for the work that we ultimately must do. These two steps—bringing people together, co-defining paths to transformation—are necessary to develop our individual and collective capacity for transformation. Done well, this will allow us to unleash the full capacity of our collective intelligence to co-create the future we long for.

I feel a need to include a cautionary note here on “gurus” (for lack of a better term). I recognize the Sanskrit word holds a positive connotation; the thing I’m trying to describe is a self-aggrandizing form of mastery in the Western context that we too often see in our movements among those who purport to be leaders… and is partly why many of us are so skeptical around this discourse of mastery and leadership.

To me there is an important distinction between masters still on the path, and masters who believe they’ve arrived. There is a quality of humility that is important: a function of curiosity and openness that distinguishes master from guru. Perhaps the relevant difference is simply this: the guru believes they have found THE answer. The master knows they have found one of many answers… with more learning still ahead.

From hierarchy to interdependence

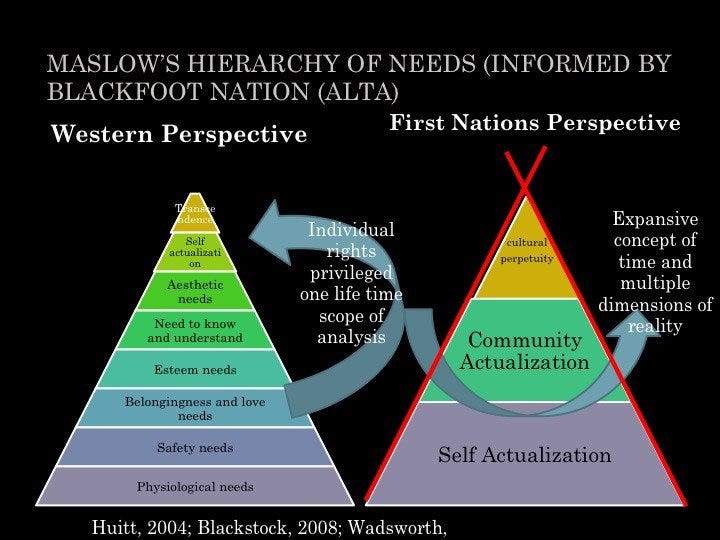

Teju Ravilochan recently offered a beautiful re-interpretation of Maslow’s famous hierarchy of needs, drawing on indigenous wisdom. He does two things, first flipping Maslow’s hierarchy (intuitively understood as a sequential linear progression) to depict it instead as more of a developmental hierarchy:

This reframe centers our focus not in the individual (as in white settler/colonial cultures), but rather starts with the individual in service of the collective… and of life itself. The goal then is not individual achievement but collective capacity… broadly understood as intergenerational and therefore a gift and responsibility from ancestors to descendants.

The second shift is to dismantle the hierarchy entirely, and to reframe it as a set of relationships that are all essential. Channeling Seneca scholar Terry Cross, he offers this insight:

Human needs are not uniformly hierarchical but rather highly interdependent.

Right. We do not ask whether the brain or the heart is more important to the body’s functioning: we recognize that both are vital. It is not a hierarchical relationship but an interdependent one.

Increasingly innovation in the “future of work” space seeks to expand on this insight. The coinage “heterarchy” seeks to capture this nuance. Reinhard Wagner explains:

Whereas hierarchies involve relations of dependence… heterarchies involve relations of interdependence.

The piece that feels important to emphasize: it’s about relationships. We build capacity in relationship: no man is an island. I loved this exquisite podcast episode with Nanci Luna Jimenez, who reminds us:

Relationships are the ongoing basis for learning.

And as we build capacity, we can tolerate more complexity… including the complexity to recognize interdependence and integrate polarities, rather than to be stuck in binaries and domination hierarchies.

Transformation is the art of building capacity

This is the conclusion I’ve been coming to. Miki Kashtan has been influential in this line of thinking for me; the Vision Mobilization Framework emerging out of her collaboration with Emma Quayle and Verene Nicolas makes this explicit: the focus of all work is to increase capacity to move toward the vision.

Which means the converse is also true: there is no transformation without building individual and collective capacity. This is why coming into right relationship with developmental hierarchies feels so important: the stakes are everything.

I’ve talked elsewhere about the three horizons framework, and how important it is to build the bridge from the world we struggle in to the world as we long for it to be: this is the work of building capacity.

I want to close with a quote from… Kanye West. It’s not often I quote Kanye, but I recently came across a line that really resonated with how I orient toward and move in the world:

I'm not comfortable with comfort. I'm only comfortable when I'm in a place where I'm constantly learning and growing.

Yes. I feel seen. I’ve never resonated with the language of ambition; it feels greedy, self-serving, ascension up a domination hierarchy. But this I do resonate with: a desire to become more fully myself, more fully human… understood always and only in relationship to others, to the nonhuman beings and world of which we are a part, and to future generations. This is a desire to move along a developmental hierarchy: is there a word for that kind of ambition?

I feel that desire as a constant longing, a call that must be answered. And my quest leads me to seek out those voices who have been on the journey before me, who have the most capacity to tolerate complexity… and to teach me. So that I can practice with others.

Whew. Lots of nuance I’m trying to untangle here… not sure if I’ve done a good job. I’d love to know what resonates, what feels triggering, and what other sources you’re looking to in trying to walk this fine line. And if you haven’t already… please consider subscribing.

In community,

Brian

Hi Brian -- I just finished reading another piece on hierarchies and it reminded me of this post of yours. Sharing it in the spirit of deepening perspectives:

https://developmentalist.org/article/hierarchy-and-its-discontents/